BERKELEY (LNS)—One man was murdered and over 200 people injured by police May 15 in the heaviest street battle in Berkeley yet over who controlled a city park.

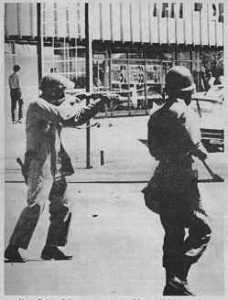

For the first time, cops used shotguns and rifles against the people. Over a hundred people were hit with birdshot, rock salt and with carbine bullets.

James Rector, the murdered man, was hit by a cop’s .12 gauge shotgun in the stomach at close range while watching the street action from a rooftop. He was 25.

The people fought back viciously, throwing rocks, bricks, bottles and anything else they could get their hands on, but as yet, no police have been shot. Over 70 cops have been injured.

To date 869 persons have been arrested and the people have called for a national support march on Berkeley to reclaim the park.

The four hour street battle was fought over a small, vacant piece of land owned by the University of California. The People decided to beautify it and make it into a “People’s Park.”

A year ago the almost one square block of land was the site of some of the most beautiful old homes in the campus area. The university bought the land for 1.3 million dollars, and demolished the houses. For nine months the land was vacant, used only as a parking lot by persons willing to risk having their cars stuck in the mud.

Then the people of the community, sick of the ugly deserted lot, got together and started working on the land. The first Sunday a hundred showed up—students, women, children, hippies, businessmen.

Everyone was so eager to work that there weren’t enough tools to go around; as soon as someone stopped working someone else asked for the pick, shovel, or rake.

Money was collected and sod was brought in, and a carpet of grass was unrolled. Trees and flowers were planted, a sandbox and swings were put in for the children, and brick walkways were laid.

Money was collected and sod was brought in, and a carpet of grass was unrolled. Trees and flowers were planted, a sandbox and swings were put in for the children, and brick walkways were laid.

During the week the park provided a place for people to rap, lie in the sun, play music and cook. Every weekend thousands of people worked in the park, and at the end of the day a “People’s Stew” was cooked, and the weary but satisfied workers would sit around and eat together.

The People had a tremendous pride in the park they were building; they saw the park as an example of “socialism in practice…”

Meanwhile, the university was sulking in the shadows. After all, the university had that piece of paper that said it owned the land, and it couldn’t let the People intimidate it. So university chancellor Roger Heyns said the land was going to be used for a soccer field (there are already four such fields in the south campus, and no parks.)

On May 14 Heyns said he would put a fence around the park “to reestablish the conveniently forgotten fact that the field is indeed the university’s and to exclude unauthorized persons from the site.”

Plans to defend the park were never formalized because the People weren’t sure exactly how the university would move.

When four hundred police moved in Thursday morning at four a.m. to clear and hold the park and the adjacent area, there were only about fifty People in the park. Only three people refused to leave, and they were arrested.

Thursday morning found the police lounging in the park, workmen frantically erecting a steel wire fence around the property, and residents and students angrily watching the whole tragedy.

People drifted up Telegraph Avenue, which was blocked off from Dwight Way to Channing, awaiting a noon rally on the nearby UC campus.

Around twelve thirty, over three thousand people assembled at the rally, while at least a thousand others had to move back down the avenue. It was the student body president speaking last at the rally who had called for people to march down and “take the park.”

At the corner of Haste and Telegraph, half a block from the park, people were met by hundreds of law enforcement officers including Berkeley city police, California Highway Patrol, San Francisco tactical squad, and Alameda County Sheriffs.

The inevitable tear gas barrage began. But this was no normal Berkeley street battle. There were at least three thousand people, including many nonstudents, straight people, and even some fraternity guys who had helped build the park, and the intensity of the fighting was greater than ever before.

They were fighting for more than a set of demands, but for something they had created.

The police could not disperse the demonstrators with tear gas canisters. People kept moving and eventually enlarged the battle scene into a thirty square block area. Determined to rout the demonstrators, the cops began to escalate their offensive

Alameda county sheriffs, equipped with twelve gauge shotguns filled with birdshot and lead pellets, fired repeatedly into the crowd. Many people in the streets were shot in the backs, others were shot standing on roofs overlooking the scene.

The battle expanded into nearby streets, but the bulk of the police force remained to protect the park. The police spread tear gas from specially equipped cars. helicopters and national guard jeeps.

They sped through the streets at very high speeds. Nevertheless, many of the cop cars were pelted with rocks.

A crowd of over a hundred people backed two policemen against a wall, showered them with bricks, and eventually chased them away.

People then moved to their car, smashing the window, turning it over, liberated the officers’ radio, uniforms, and other equipment from the burning vehicle.

The usual ebb and flow of street battles was missing—the fighting remained intense until four o’clock. Even in adjacent residential areas the fighting was heavy, as police shot tear gas canisters into houses and shot people on rooftops.

Many residents, both young and old, aided people, offering first aid and the relative shelter of their homes.

The day’s casualty figure reflected the intensity of the battle. At least sixty-six people were treated at local hospitals including five police, one of whom was stabbed in the chest.

Over one hundred people went to the first aid center at The Free Church, and over sixty officers were treated at the police first aid station. Two reporters were injured by shotgun pellets, and at least five people were wounded by thirty caliber bullets.

At six p.m. Governor Reagan, at the request of the city of Berkeley, called out the National Guard, and imposed a curfew from ten pm to six a.m. Members of the forty-ninth infantry brigade, a select reserve force with experience in riot control, assembled in undisclosed armories.

The governor’s declaration also prohibited any public assembly, rally or gathering anywhere in Berkeley. As people began to gather for a noon-time rally on Friday, the highway patrol moved in to clear the steps at Sproul Hall.

Six thousand people then marched to the Shattuck Avenue commercial center of Berkeley. When the highway patrol sealed off that area, they came back to the campus, held a meeting, and decided to return to the streets.

The National Guard stood watch over the marches, but was reluctant to act against the people. When ordered to seal off a street, they moved far more slowly than the cops, leaving people alone for the most part.

A revealing incident took place when a good looking girl walked past a Guardsmen. A cop yelled to him, “Why didn’t you get a little piece as she walked by?” The Guardsman gave the cop the finger.

Despite the Guard and the Governor’s prohibitions, almost four thousand people stayed in the streets. They eventually dispersed, but they promised to return.

Related

- See other stories in this issue.

- “Berkeley USA, 1969” by Art Johnston, FE #81, June 12-25, 1969.