a review of

The Daring Life and Dangerous Times of Eve Adams (with the original text of “Lesbian Love”) by Jonathan Ned Katz. Chicago Review Press 2021

Eve Adams died in Auschwitz, the Nazi death camp, because the U.S. government could not countenance the writer of a lesbian love story (among her other transgressions) to reside in the U.S.

Eve’s sweet little stories in “Lesbian Love,” self-published in 1925, resulted in her arrest, trial, conviction, imprisonment, and deportation for publishing an “indecent book” and allegedly attempting to have sex with a policewoman assigned to entrap her.

Eve’s sweet little stories in “Lesbian Love,” self-published in 1925, resulted in her arrest, trial, conviction, imprisonment, and deportation for publishing an “indecent book” and allegedly attempting to have sex with a policewoman assigned to entrap her.

Reading Eve’s stories now, what stands out is their innocence: women gazing passionately at each other, kissing, stroking each other’s breasts, whispering lovingly. There are a few sketches of graceful nudes in various embraces. Stories of women who longed for one another provoked a torrent of government lies, exaggerations, and paranoid fantasies of what women might do together and how it might damage proper social order.

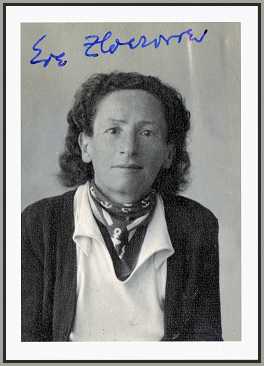

Eve Adams was born Chawa Zloczewer in 1891 in Poland, and immigrated to the U.S. in 1912. The young Jewish woman ran lesbian-and-gay-friendly tea rooms in New York and Chicago, sold radical publications, and hung out with anarchists. Eve ran afoul of the U.S. Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924, which had clauses restricting immigration based on “moral turpitude” and “disorderly conduct.”

After serving a harsh jail sentence, Eve was deported, struggled to make a living for a time in Poland and later in Paris, was arrested by the fascists in the south of France in 1943 with her lover Hella Olstein Soldner, and was murdered in Auschwitz. Eve was 52 years old, Hella was 38.

Eve’s role in the anarchist movement consisted largely in selling literature as a traveling salesperson. She journeyed from New York to San Francisco, selling anarchist, IWW, communist, and socialist publications. It appears that Eve was one of the legion of working people who did the necessary labor of organization and distribution of anarchist literature.

This is a fascinating aspect of the anarchist movement of that era and I wish there was more in this book about how she did that work. Katz associates Eve with a community of traveling women, restless and resistant to conventional expectations, called “hoboettes.” Yet it is not clear that the other unfortunately-named hoboettes also sold radical literature.

I imagine there was a network connecting anarchist communities to people like Eve who provided political literature that was excluded from the mail by the Comstock laws. One of plethora of government agents, reporting on Eve’s activities in Los Angeles, noted her presence in Italian, Mexican, and Spanish neighborhoods there, suggesting she had connections in those anarchist communities. More work on these networks linking publications to reading publics would shed welcome light on anarchism’s on-the-ground workings.

Jonathan Katz has done a remarkable job of researching the life of Eve Adams. He has tracked down an impressive span of sources, and diligently followed numerous directions of research, even if, in the end, they led nowhere.

His book raises intriguing questions about how we tell lost stories, or the stories of lost people. What counts as data and how do we assemble it? Katz is scrupulously old-school. He combines extensive research and documentation with a cautious attitude toward his sources.

While he is willing to speculate on what Eve may or may not have thought, he never comes close to fictionalizing her life or telling more than his sources can firmly support. His approach produces a different reading experience than that of writers who are more willing to imagine the lives of neglected historical figures by extrapolating from available sources.

Despite Katz’s hard work and best intentions, Eve’s story is a bit flat. The reader, at least, this reader, does not feel connected to her. Lacking much access to her inner life, I have trouble interpreting her actions, or figuring out what to think and more importantly what to feel about her.

Her relation to Ben Reitman, an anarchist doctor and one of Emma Goldman’s lovers, is an example of a puzzle that needs more personal context to be fully coherent. Reitman was a well-known cad. His letters to Eve mix affection with insults, often in the same paragraph. Why did she keep turning to Reitman for support as her situation in France became increasingly desperate? Was it poor judgment or just a paucity of friends?

Eve’s work selling radical literature across the country put her in touch with a substantial population of radicals. She knew Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Eulalia Burke of the IWW, and many others. Why didn’t she have other comrades who could have helped her? Katz Suggests that Eve was too working class or too Jewish for the up-scale literary salons in Paris such as those of Gertrude Stein, Alice Toklas, or Natalie Barney. That makes sense, but Eve also knew Henry Miller, Anais Nin, and other bohemian denizens of that city. It is painful to ponder why Eve and her beloved Hella had no one else to turn to, other than the hapless and unreliable Reitman, as the fascists closed in on them.

Another puzzle is Eve’s relation to anarchism. Was it a political commitment, or just a job? Katz describes Eve’s politics this way:

“Eve’s own radical politics, never explicitly defined by her, probably included an evolving, amorphous mixture of anarchist, socialist, communist, left-libertarian, and militant labor ideas about work, class, and the economy, culture, gender, and sexuality. Eve’s politics are probably best described as left radical.”

Perhaps anarchism was just a hanger-on for her, part of the fringe bohemian cultural scene of New York and Chicago, a bit more gay-friendly than most, but not a serious element of life? If her understanding of anarchism was superficial, that might explain her confusing attitude and actions toward her own legal jeopardy. She did not appear to understand the danger she faced, both imprisonment and deportation, until it was too late. Was she utterly clueless, or just lacking resources? The anarchist movement had its own lawyers, when needed. Eve certainly needed one.

There were stirrings of pro-gay and lesbian activism in anarchism in that era. Margaret Anderson, co-editor of The Little Review, spoke out publicly in support of homosexuals. Anarchist printer Joseph Ishill had earlier published Oscar Wilde’s Ballad of Reading Gaol. Goldman spoke publicly in support of the “intermediate sex.” Berkman’s time in prison brought him to tender appreciation of love between men, as he wrote in his powerful autobiography Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist. Even though the anarchist movement was much weakened by the arrests and deportations of the post-World War I red scare, the lack of connections between the remaining movement and Eve’s desperate, ineffective struggles is disturbing.

Katz emphasizes Eve’s capacity for self-creation—her new identity, appearance, and adventures. Her clever name—Eve + Adam—was an androgynous new beginning. Katz casts a wide net to frame Eve’s story He shows what else was going on in literary, political, racial, sexual, national and international contexts, giving Eve Adams’ life needed context. He is right that “Lesbian Love” was a brave title and that it made a great deal of trouble for her. He calls Eve “one of the country’s first lesbian justice activists” and that is a history worth recognizing.

Kathy E. Ferguson teaches political science and women’s studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She is currently writing a book on anarchist print culture in the U.S. and Great Britain from the Paris Commune to the Spanish Revolution.