a review of

a review of

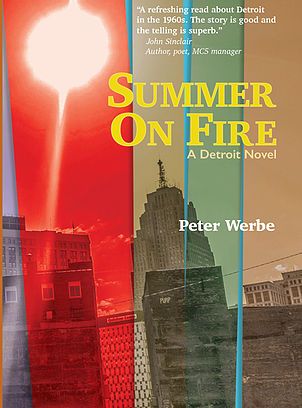

Summer on Fire: A Detroit Novel by Peter Werbe. Black & Red 2021

Summer on Fire, a debut novel from long time Fifth Estate staff member, Peter Werbe, takes place during seven weeks in 1967, the year I was born, during the months I lived in my radical mama’s belly. So, I definitely need the narrator’s front seat to those tumultuous times.

With this captivating, rollicking read, Werbe clears the pot-filled air of so many misunderstandings that a Gen X hippypunk like me, or later younger radicals could easily imbibe either the 1960s or the story of the Fifth Estate. Even though it is 1967, you are not going to San Francisco with flowers in your hair.

In fact, any trite trips about the scene you may have entertained about the late ’60s period are blown to bits by this badass book. Of course, you will see remnants of what your grandparents forgot to tell you. The sex and drugs are definitely there, although not too salacious or sensational. During my twenty years as an active member of the Fifth Estate collective beginning in 1989, only a handful of our frequent writers were regularly publishing books.

While I arrived too late for the works of Fredy Perlman as they came off the press of the Detroit Printing Co-op, I witnessed the processes leading to the publication of FE staffer David Watson’s important texts such as Beyond Bookchin and Against The Megamachine.

But, I was still waiting for my friend Peter’s first book. When I imagined his first effort, however, it was going to be a career-spanning collection of his essays, not a novel. But, his historical and incendiary fiction, that he insists is bigger than himself, is no less a product of years of collaborations and relationships based around the Fifth Estate than his essays would have been.

The audacious, realistic tone of this tale avoids too much analysis and refuses any moralizing. Although violence is central to much of the plot and most of our learning in Summer on Fire, it is never amplified antagonistically nor condemned cathartically. We just see how the revolutionaries of that time both opposed an imperialist war and yet fought like hell for their own imaginations and integrity.

Summer On Fire doesn’t so much fan the flames of urban rebellions like those reborn last summer across the U.S. and elsewhere following the brutal state murder of George Floyd, but it brings you close enough to the fire to warm your hands on the rage of the repressed and the rebellion of the oppressed.

All this is set inside the mental and emotional fire rendered hotter by the expanded consciousness and explosive life choices of the counterculture. Most readers will get a greater understanding of why we fight, what we are fighting against, and will leave the book with their inner fire kindled for more.

If an overarching history of the FE is ever attempted by an anarchist scholar down-the-line, allow this interpretation of Summer On Fire to at least dabble in our origin story.

The roots are not in the philosophical debates about the fundamental alienation of life under capital or in our embrace of the liberating core in primal lifeways, as a robust alternative. The roots are not in long, boring, 8-hour consensus meetings where everything is discussed and nothing really decided. The roots are not even necessarily in the movement against the Vietnam War and the summer rebellions so vividly described in these pages.

The roots of this revolutionary magazine are not in ideologies so much as in experiences, like taking LSD, riding motorcycles through the streets of the Motor City, dancing almost all night at the Grande Ballroom, and still getting up the next morning to resist the war which claimed so many lives in imperialism’s invasion and destruction of Indochina.

But rather, we meet Paul and Michele, a married couple in their late 20s as the central characters, much older than many of their revolutionary comrades of the time, eating lots of vegetarian cuisine, loving and arguing and traveling, just living an unpretentious working-class life in Detroit’s imploding industrial, concrete wasteland. Paul and Michele live this life with such revolutionary joy and psychedelic wonder that it will give most readers pause to question our own currently less-enchanted existence and plodding pandemic life of endless Zooms and spinning Netflix queues.

The raw details of this fictionalized take on that fabled summer of 1967 in Detroit go far beyond so much of what you thought you knew about the New Left and its radical possibilities of the time.

When I first got a pre-publication PDF to read in preparation for this review and to create a 60-song playlist/soundtrack that the author and I co-curated, I devoured the book over a few days, and was sad when it ended. I laughed, cried, and got warmed to my core with the flames of revolution. For the soundtrack and historical footnotes for the book, go to Peter’s web site at PeterWerbe.com.

Although anti-authoritarian resistance remains for us on many fronts today, as it did then, it’s easy for aging radicals to get either complacent or discouraged. If you sometimes find yourself with me in that camp, Summer On Fire is just the injection you might need.

This beautiful book helped me rediscover and remember my Detroit roots and why these struggles are ongoing against the authoritarian mindset that our main characters defy with every fiber of who they are, with joyful, defiant, revolutionary, anarchist desire.

Sunfrog lives somewhere in middle “Tanasi,” on the traditional land of the Cherokee and the Yuchi tribe, also used by Shawnee, Chickasaw, and Muscogee Creek people.

SPECIAL OFFER: $25 for book plus one-year Fifth Estate subscription or renewal.