On May Day 1919, in the immediate aftermath of World War I, a general strike began that shut down all economic activity in Winnipeg, Canada. The general strikes that took place in Glasgow, Scotland in January 1919, in Seattle in February 1919, along with the Winnipeg strike remain some of the high watermarks in North American working class history.

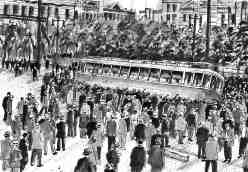

David Lester’s graphic novel, 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike, provides a striking visual introduction to the history of the strike that during six weeks, Thirty-five thousand workers brought the city to a standstill.

The strike was an act of solidarity. At the time, Winnipeg was primarily a railroad junction with thousands of workers employed in the yards of the Canadian Pacific Railroad (CPR). Smaller shops supplied the railroad with a variety of inputs, including steel. The rail yards were unionized, but the smaller contract shops were adamantly non-union.

When the owners of the smaller metal shops refused to bargain with a coalition of unions in the industry, the Metal Trades Council, the unionized workers of Winnipeg walked out in support. They were soon joined by thousands of other workers in smaller, non-unionized workplaces and the general strike became total. The strike Committee issued permits so that essential food could be delivered to grocery stores.

In the end, on June 21, 1919, specially deputized police joined soldiers in crushing the strike, after a tram operated by a scab was toppled by a march of pro-union veterans.

The strike leadership was composed of a coalition of militant union activists and the moderate leaders of the established unions. The unions represented in the Metal Trades Council were business unions, many of them Canadian sections of the American Federation of Labor.

On the other hand, some of the strike leaders were rank and file radicals, who were intent on creating a new federation of independent unions, the One Big Union or OBU, as the IWW frequently referred to itself.

The demands of the workers were quite modest. The strikers demanded union recognition, a substantial pay increase and a shorter work week than the standard 55 hours. On the key demand, union recognition in the contract shops, the strike failed, as these remained open shops.

The history of the Winnipeg strike raises broader issues concerning general strikes. It lasted far longer than the other general strikes of that year. For most of the six weeks, the strike remained solid and disciplined. Furthermore, the strike demonstrated the power of the working class and its ability to disrupt production for an extended period of time. Nevertheless, the workers failed to win their demands.

One reason for this failure is that the strike remained largely limited to one city, although brief solidarity strikes did take place in several other Canadian cities. Only Vancouver organized a lengthy general strike, but it began in early June, a month after the Winnipeg strike had started. More importantly, the Canadian Pacific continued to operate transcontinental trains through Winnipeg, as workers in the operating unions declined to join the strike.

It is very likely that a strike that disrupted the sole railroad linking eastern Canada with the western provinces would have quickly drawn the federal government into the conflict. This raises the issue of state power. A general strike is an effective method of putting pressure on an employer or government official, but a successful revolution still requires the undermining of the morale and cohesion of the police and the military.

The Winnipeg general strike and the other ones in 1919 are significant historical models, but can they still be an effective strategic option in the late capitalism of the 21st century?

Solidarity strikes can shake the system without directly challenging capitalism itself. Another type of general strike, one that starts with a set of demands that could hold across all sectors of the workforce, has a more radical edge as its premise. In the case of the 1919 Glasgow strike, the Clyde Workers Committee, led by revolutionary socialists, initially called for a general strike to establish the 30-hour week. This was a demand that had already been raised by the IWW. Although the demand was later watered down to a 40 hour week, it was clear that strike leaders were intent on projecting a prefigurative program, looking forward to a new and different society.

A third type of general strike, the political general strike, has the greatest potential for presenting a direct challenge to the existing system. Political strikes raise demands that specifically target the state.

Often such strikes focus on issues related to militarism and war. Prior to World War I, many groups on the Left pledged to organize a general strike to stop the war before it started. Although strikes such as this did not occur, the women of Petrograd initiated a general strike in March 1917 that led to the overthrow of the Russian tsar by demanding an immediate end to the war.

Recently, climate change activists have discussed the possibility of a general strike around environmental issues. There is some way to go before such a strike could be effective, but it is interesting that the issue is being seriously discussed.

General strikes can be an effective tactic. They can solidify class unity, raise important demands, and demonstrate the power of a unified working class. Yet they are not the only means to move forward.

An aroused populace will usually engage in a range of militant tactics, all of which can help propel the struggle toward a revolutionary turn. Looking at Petrograd in 1917, women began by organizing marches in defiance of the authorities. As these demonstrations pulled workers out of the arms factories and into the streets, the czarist regime began to collapse.

Recently, the Yellow Vests in France show the power of mass marches. Marches can be effective, but so can occupations, as the Occupy movement of 2011 demonstrated. Marches and occupations are tactics that can build the momentum needed to sustain a successful general strike.

There is no general rule for which tactic will be successful at a particular moment of time. Each tactic can reinforce the other in the effort to build a movement for fundamental change.

Eric Thomas Chester is the author of The Wobblies in Their Heyday, a history of the Industrial Workers of the World during the World War I era, and Yours for Industrial Freedom, an anthology based on letters introduced by the prosecution during the 1918 IWW Chicago conspiracy trial.

Related in this issue

“Comics, Graphic Novels, & the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike,” FE #404, Summer, 2019