A hundred years ago, in September 1918, more than a hundred leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were convicted of conspiracy to obstruct World War I. The trial marked a critical turning point for the union and the Left. In marking this centenary, we remember the Industrial Workers of the World as the most successful organization holding to a radical vision in U.S. history.

The experience of the IWW provides many positive models for radicals a hundred years later. Wobblies were not involved in electoral activity. Instead, they focused their energies on organizing disciplined grass-roots direct action. At the same time, the IWW condemned unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) for their close ties to the Democratic Party, a problem that continues to this day.

The IWW also had a holistic vision of its role as a radical union. It did not concentrate exclusively on workplace organizing, but also opposed militarism, imperialism, and racism. Furthermore, the importance the Wobblies, as IWW members were known, gave to the development of an alternative culture is an exemplary lesson to contemporary radicals.

Cartoons, poems, and songs spoke to common themes and helped create a viable alternative space for those in conflict with the corporate mainstream. Martyred Wobbly Joe Hill’s sarcastic parodies of popular ditties and Salvation Army hymns remain popular to this day. Hill also was among those who recognized the importance of the IWW bringing more women into its ranks and encouraging them to become union leaders.

Founded in 1905, the IWW struggled to consolidate a base of support within working class communities. World War I changed the context within which the union organized. The global conflict led to an economic boom, as the United States produced a vast supply of the resources needed for the war effort.

In April 1917, the United States entered the war and, soon after, the government began conscripting men into the army. The war and the draft were extremely unpopular, especially in the Western states where the IWW was most active.

Union membership rocketed, as the IWW’s membership grew from 15,000 to 150,000. In the spring and summer of 1917, timber workers in the Pacific Northwest and copper miners in Arizona had organized effective, militant strikes.

The strike of timber workers began in northwestern Montana in April 1917. It quickly spread throughout the Pacific Northwest as thousands of lumberjacks quit work and brought production to a standstill. Many of the demands related to the miserable conditions in the timber camps, but there were also calls for an eight hour day and a union hall for new hires.

The strike was remarkably effective. Union leaders insisted that those on picket lines had to be disciplined and non-violent. Strikers were urged to avoid alcohol, a major problem among timber workers.

From the start, authorities were intent on breaking the strike. At the behest of Montana’s governor, President Woodrow Wilson dispatched troops to the first camps on strike. Soon soldiers were detaining IWW activists, holding them for an indefinite period without specifying charges.

As the strike spread, the military began widening the scope of detentions. A person who merely joined a picket line could be detained for weeks in a makeshift bullpen, where food was scarce and sanitation minimal. In August 1917, James Rowan, the secretary of the Lumber Workers’ Industrial Union #500, called for a general strike throughout the region. He and the other union leaders were detained and the strike finally collapsed.

The use of troops to crush picket lines and detain hundreds of peaceful strikers for weeks on end represented a serious threat to fundamental rights. These were actions taken without even a facade of legality by a government dependent on military force

As impressive as the strike of timber workers was, the strike of copper miners had an even greater impact. Copper was an essential component in the production of munitions.

In the early summer of 1917, the Metal Mine Workers’ Union #800 organized miners in camps around Arizona, the most important of which was in Bisbee. A key point in the organizing drive was the call for a six hour day. This demand was seen as a way of bridging the vision of a future society with the immediate needs of the miners.

On June 27, 1917, the Bisbee branch went on strike, with other camps in the state soon joining in. In addition to demands related to health and safety, the union called for a substantial increase in the pay of topmen who hauled the ore that had been brought to the surface. Most were recent immigrants from Mexico and paid substantially less than the miners.

Once again, the strike was disciplined and non-violent. Every day, mass rallies were held where IWW speakers presented the basics of the class struggle and the need to build a new cooperative society. Union leaders also stressed that the six hour day would be placed on the table once the current strike was won.

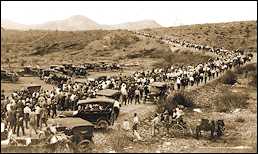

On July 12, 1917, unable to break the unity of the miners, an armed vigilante gang organized by the copper corporations rounded up two thousand strikers at gun point. They were forced onto crammed cattle cars and dumped in the desert hundreds of miles from Bisbee. For months, Bisbee remained under vigilante rule. Those deported were taken to a military base in Columbus, New Mexico, before being slowly released.

Governors in the Western states denounced the IWW as a threat that had grown beyond the capability of the states to suppress. Shortly after the deportation, President Wilson decided that the union had to be crushed. Once this decision was made, the federal government implemented a coordinated attack on the IWW beginning in 1917, with a blatant disregard for even formal Constitutional rights. Wobbly newspapers were suppressed, union halls raided, and documents indiscriminately seized.

The Justice Department prosecuted union activists in three different show trials. In the most important one, held in Chicago, nearly 100 union leaders, including Big Bill Haywood, the IWW’s general secretary, were convicted in 1918 of violating the Espionage Act for opposing World War I and served lengthy sentences in a high security penitentiary.

The IWW was not prepared to cope with this onslaught. Membership plummeted, as the union devoted its resources to defending itself from government repression. Even after the war ended, the union was barely able to sustain itself.

In 1924, the IWW underwent a bitter split rooted in personal and political divisions that had arisen earlier during the government’s assault on the union. Only in the 1960s did a new generation of radicals revive the IWW. The current day IWW continues to organize those stuck in the gig economy.

Finally, the trampling of basic rights by the administration of Woodrow Wilson shows that we cannot rely on liberal politicians to defend civil liberties. Nor can we rely on the judicial system, whatever its political complexion. Only an aroused populace can protect the right to dissent from government attacks.

Eric Thomas Chester is the author of The Wobblies in Their Heyday, a history of the Industrial Workers of the World during its most vibrant period, the World War I era, and Yours for Industrial Freedom, an anthology providing insight into the IWW as it really was based on letters introduced by the prosecution during the 1918 Chicago conspiracy trial.