During his visit to Chile in January 2018, Pope Francis officiated a mass in the Araucania region—the ancestral territory of the Mapuche people.

The night before, unknown individuals burned three forest company helicopters, three churches, and a school. Fliers demanding the liberation of Mapuche political prisoners were found nearby.

So far, no one has been charged in connection with these acts.

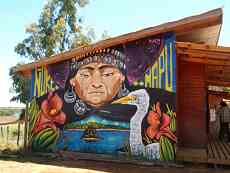

The Mapuche are indigenous people of South America who have been involved in a long struggle for cultural autonomy and territorial independence since the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century. They call themselves the “people of the earth,” which is the meaning of the word Mapuche in their language. Their ancestral territory, known to them as Wallmapu, stretches across the Chile-Argentina border.

From 2001 on, the Chilean state used the Pinochet-era Anti-Terrorism Law against the Mapuche. Since then, police and landowners have killed sixteen Mapuches. One of the most controversial cases was the assassination of the activist Matias Catrileo, shot in the back by an officer in 2008.

In 2013, Chilean President Sebastián Piñera’s government prosecuted protesters for Anti-Terrorism for the death of landowner Werner Luchsinger and his wife Vivianne Mackay in an arson attack which occurred during a protest in commemoration of Catrileo’s death.

Machi Francisca Linconao and 10 other Mapuche leaders were charged. While some were convicted, Linconao spent nine months in jail awaiting trial. After starting a hunger strike, she was transferred to house arrest. When she was finally brought to trial, she was acquitted of all charges due to lack of evidence.

Machis are healers and spiritual figures that perform shamanic rituals—such as the Machitun and Nguillatun, the two main Mapuche ceremonies of healing and prayer for purification and wellbeing. Both men and women can be machis, and their role is key to protecting the ancestral territory—Wallmapu—and all its beings, including the ancestors.

When machi Francisca Linconao tried to talk with Pope Francis during his visit, she was not allowed to enter the cathedral and was detained. Activists think this was in retaliation for her success in the protection of a menoko—a sacred place with biodiversity—against commercial logging.

The so-called Mapuche problem is the criminalization of a culture that resists assimilation and fights for survival. Chilean law criminalizes any action to claim and recover Mapuche land and is used to persecute and imprison activists. Police have legal prerogatives to enter homes in the communities and detain prisoners for extended periods of time without trial. The only solution sought by the state and corporations seems to be ethnocide.

Through the normalization of violence, public opinion has been politically neutralized, while the trauma inflicted on Mapuche people is personal, collective, and historic.

Before the Spaniards arrived in the 16th century, the Incas tried to colonize the Mapuche and integrate them into their empire, but failed. After the conquistador, Francisco Pizarro, took control of the centralized Incan empire in 1533,

Spaniards colonized the south of the continent. In 1541, they founded the town of Santiago de Nueva Extremadura to honor the Catholic Saint James, the modern capital of Chile.

In September of that year, a Mapuche attack destroyed much of the newly established town. Inés de Suárez, a female conquistador, commanded 55 Spaniards plus native allies against the attack in the absence of Pedro de Valdivia and his army who were exploring the south. The Spaniards had captured seven hostage Mapuche lonkos (indigenous chiefs). De Suárez decapitated one and ordered the decapitation of the six others. Their heads were hung on the town wall to demoralize the Mapuche warriors. The tactic was effective—the Mapuche fell back.

Santiago was rebuilt and the war against the indigenous people continued.

The Spaniards renamed the Mapuche “Araucanos” and their home territory of Wallmapu “Arauco.”

The town of Concepcion was founded about 300 miles south of Santiago in 1550. From there the war against the native people was planned and directed.

The Mapuche continually organized strong resistance through both guerrilla warfare and large-scale battles in what became known among the Spanish as the Arauco War. This conflict was so costly for the Spanish crown that Mapuche autonomy was finally recognized through the Treaty of Quilin in 1641.

The peace agreement established the area south of Concepcion as an autonomous territory where indigenous people were free and exempt from slavery. However, the Mapuche agreed to accept Philip IV of Spain as their king and leave at peace Catholic missionaries crossing the border into Mapuche territory. This agreement was, in fact, the continuation of war by other means.

After Chile’s independence from Spain in the early 1800s, the Mapuche were classified as Chilean citizens. Although the autonomy of their territory was supposedly recognized, the Chilean state annexed it through a military campaign of occupation and acculturation called Pacification of Araucania between 1861 and 1883.

Mapuche people were displaced, marginalized, and discriminated against, becoming cheap labor in the countryside before their mass immigration to urban areas from the 1940s to the early 1970s.

In spite of this depressing scenario, the Mapuche were able to retain their culture, language, and dreams.

During socialist Salvador Allende’s 1970-1973 presidency, some Mapuche land was returned to their communities through agrarian reform. But this was reversed after the military coup of September 11, 1973, that installed Pinochet dictatorship that lasted 17 years.

Much of Wallmapu was clear-cut and planted with monoculture crops. Besides lumber, entrepreneurs extracted hydroelectric power and agro-industrial produce, dispossessing the local communities and breaking the Ad-Mapu—the social, spiritual, and ecological norms that govern all Mapuche interactions.

While Chile was transitioning to democracy in the 1990s, two groups began taking action to recover the land from forestry companies and ranchers. The pro-independence Consejo de Todas las Tierras, formed in 1990, and the radical Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco (CAM), began in 1998, initiated intense political, legal, and communal activity, from hunger strikes to the transformation of timber plantations into gardens, reinvigorating Mapuche culture.

There are four basic levels to Mapuche society. The first level is the family and extended family which constitute the basic productive unit.

The second level, the lof, a village community, consists of familial clans, which coexist on a mutual land base. The land belongs to the community and it is used collectively. However, each family remains autonomous while the whole community makes decisions together in assemblies or trawün. In each community there is a lonko or chief. Lonkos are often men, but they can be women.

The third level is the revue, which is a voluntary association of villages in a contiguous local territory for political and ceremonial purposes.

The fourth level is the ayllarewe, which is a group of nine revues that govern a territory, normally around a river basin.

This complex social organization has existed through the centuries regardless of who is in political power.

As 19th century French anarchist Anselme Bellegarrigue put it, “people waste their time and prolong their suffering when they make the government and political disputes their own.”

Perhaps this explains why the Mapuche did not support the coalition of the lesser evil, namely the progressive one, in the last election. They have gone instead into the reinforcement of their autonomy, revitalizing their culture.

I visited Wallmapu in the winter of 2017-18. During my visit to the community near Budi Lake, I saw coops, community assemblies, organic crop fields, nurseries to bring back indigenous flora, and a bilingual school.

As Viviana Calfuqueo, a member of an artisan women’s group and cultural leader in designing community livelihoods programs, put it, “when I sit at the loom, the whole world vanishes away.”

The Mapuche are sound and strong. They have never been decisively defeated, and they keep fighting for a life in connection to their land in autonomous self-governance.

Jesús Sepúlveda teaches at the University of Oregon in Eugene. He is the author of eight collections of poetry and three books of essays, including his green-anarchist manifesto, The Garden of Peculiarities, and his book on Latin American poetry, Poets on the Edge.