There is a near cottage industry of leftists penning engaging, sometimes lurid, always vivid, prognostications of impending social, political, economic, and ecological doom.

Websites like Counterpunch and Common Dreams, for instance, have been prophesying for several years that a war on Iran is imminent due to the fact that, alternately, a US destroyer moves to the region (2006), oil prices rise (2007), an admiral retires (2008), or, the ubiquitous favorite, the Bush Administration is simply insane. Each one of these omens indicates there will assuredly be war, maybe tomorrow.

Websites like Counterpunch and Common Dreams, for instance, have been prophesying for several years that a war on Iran is imminent due to the fact that, alternately, a US destroyer moves to the region (2006), oil prices rise (2007), an admiral retires (2008), or, the ubiquitous favorite, the Bush Administration is simply insane. Each one of these omens indicates there will assuredly be war, maybe tomorrow.

These special capacities for clairvoyance are also applied to the domestic front, grimly and confidently warning in 2003 of an inevitable draft should the war on Iraq worsen. There are also similar predictions that not only is the economy collapsing, but that an unprecedented “tsunami” of economic horrors, beyond the reach of every known metaphor, is upon us.

Did the stock market fall today? Vindication! Did it rise? Aha, the calm before the storm. It is not to completely deny the validity of these accounts to observe that their entertaining silliness — less analysis and reportage than geopolitical soothsaying – reveals and obscures several important problems.

In his Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord, notes that, “Those who are always watching to see what happens next will never act: such must be the spectator’s condition.” These self-indulgent depictions of looming disaster, indeed, embody pure spectatorship, making individual agency or even counterargument irrelevant. Sit and watch as the tidal wave approaches. Isn’t it beautiful/horrifying?

Yet another false alarm?

These are expressions of a defeated left that knows not what to do and has no confidence in itself, so it has decided to watch and hope. Yet another false alarm? Don’t worry; it will happen soon, they have to believe. It is noteworthy that these prophets do not care that they’ve harmed their credibility through so many years of false predictions; doomsday is their religion.

These predictions are dubious not because they are always wrong in particular, but because they are right in general. Like boys crying wolf, these warnings are correct that war and recession are inevitable. But they are inevitable not because an admiral retired or the price of oil went up. Rather, war will occur, though nobody (certainly not these fortunetellers, whose rate of accuracy makes football handicappers look like serious scientists) knows exactly when, because waging war is what states do.

War, as oft and correctly stated, is the health of the state. War is required to tear down obstacles to capital accumulation, open, create and protect markets, prime the economy, thwart rivals, concentrate political power, distract and disarm domestic criticism and rebellion, strengthen national ideologies and attack labor, among other things. The dogged attention on stopping the next war ignores that, so long as there are states and capitalism, war is inevitable.

Interestingly, the frequent characterization of the Bush Administration as crazy fulfills stated US propaganda aims. In a frequently quoted, but apparently forgotten 1998 paper, the Pentagon counseled that the US should try to portray it-self as being not “fully rational and cool-headed.” Rather, the Strategic Command advised, US foreign policy goals would be best achieved through the projection of an “irrational and vindictive” persona, intending to intimidate real or imaginary opponents in order to get its way with the least possible resistance. The fact that, in addition to the current president, the three major presidential candidates have all threatened massive bombings of recalcitrant nations suggests that their “irrationality” is, from a state perspective, not irrational at all, but standard policy.

The US naturally has concerns over the prospect of Iranian power and, just as obviously, is quite willing to employ war as a continuation of its politics. While speculation on specifically what a state will do and when it will do it is mostly guesswork, the fact is that as it now stands, the US military is badly overextended. Beyond its deteriorating equipment and exhausted troops, the military has little strategic leverage due to its engagement in Iraq.

An attack on Iran would immediately make US soldiers more vulnerable than they already are due to probable retaliation by Shiite forces in Iraq that have mostly refrained from engaging the occupying army. It is more likely that it is this very strategic and tactical weakness that is accounting for increased US bellicosity, as the administration hopes that the threats of a putatively irrational lame duck president will achieve the political goals that its military cannot. In this regard, leftist warnings about the trigger-happy president and his pending attack on Iran do the government’s bidding.

Regarding the ongoing war in Iraq, nationally syndicated columnist Norman Solomon critiques the “path of least resistance” arguments of the anti-war movement, noting that the propensity to criticize the war for being “unwinnable,” a rhetorical ploy designed to appeal to US patriotism, has found itself snookered when faced with media propaganda that the military’s “surge” “is working.”

Solomon correctly stresses that wars should not be criticized for being unsuccessful, but because they are state mass murder waged for empire. Similarly with capitalism; criticism should not be limited to its crises. Recessions, and for most of its history, depressions, are part and parcel of capitalism. A fevered focus on anticipating the next recession frequently implies that economic downturns are avoidable or result from individual or corporate misdeeds rather than capitalism’s systemic definitions.

Criticism of capitalism should not point to its (prospective) “bad” elements through forecasting and bemoaning depressions, but instead stress the intrinsic relationship uniting capitalism’s booms and slumps. The inherent exploitation and wastefulness of capitalism is ever present if one is only willing to look, not least during its booms. A system of speculative-based perpetual expansion and rapacious consumption predicated on the extraction of profit from wage labor should be loathed not seasonally, but always.

Moreover, the hyperbolic tones of these warnings are ill suited to describing the evolution of depressions. Forgotten is that the Great Depression did not arrive all at once with the stock market crash, but instead developed gradually in fits and starts throughout the early 1930s. Similarly ignored is that a rather intense recession has wracked the US economy, on and off, since 1973.

Profit, Robert Brenner demonstrates in The Boom and the Bubble, has diminished every decade since the end of the postwar expansion. The marked decline in the standard of living for all but the wealthy over even just the past several years should raise suspicion at those looking away from the present in the name of proclaiming that soon it’s really going to be bad.

Notwithstanding their sci-fi entertainment value, attempts to forecast doomsday scenarios preclude a meaningful apprehension of the horrors of the present. Raoul Vaneigem writes in Revolution of Everyday Life that whatever the future brings, it will be natural, as it will be ours.

Indeed, while many take famous dystopian novels like Huxley’s Brave New World as dire warnings to be heeded, they can be more critically appreciated as caricatured depictions of the present. Fixating on future woes displaces attention from critical analysis to feelings of dread.

What gets lost is that, boom or bust, daily life for most people in the world today is one of toil, suffering, alienation and pain, if not worse. The challenge should not be to try to wake the somnolent with chimeras of ever worsening suffering, but to denaturalize the present until it becomes apparent and unbearable. The nightmare is already with us. If that is not understood, then that is the problem.

Joshua Sperber can be reached at jsperber4 ( at ) yahoo ( dot ) com. See more of his writing at http://voidmirror.blogspot.com/ .

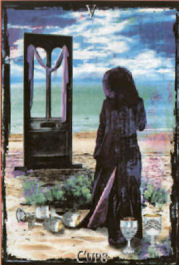

Editors note on graphic accompanying article: Tammy Wetzel. Five of Cups, part of the Divine Feminine Tarot Deck, a work in progress. The deck is all female and each card is a digital collage using her photography, as well as scanned objects.

Each card is representative of a stage, cycle or influence in women’s lives. The door in the image is from a photo taken in the New Orlean’s French Quarter and the beach is on Cape Cod. See more at

http://www.tammywetzel.zenfolio.com [no longer available]