When I was first asked to write an obituary in the Fifth Estate for Dr. Albert Hofmann, who passed away on April 29, I felt conflicted. I was not wrestling with how to reconcile his contributions to neurochemistry and the politics of liberation; these seemed self-evident.

When I was first asked to write an obituary in the Fifth Estate for Dr. Albert Hofmann, who passed away on April 29, I felt conflicted. I was not wrestling with how to reconcile his contributions to neurochemistry and the politics of liberation; these seemed self-evident.

Rather, the question was how to write objectively about the father of LSD without talking about my personal relationship to the worlds he opened for me and millions of others.

I have come to the conclusion that I cannot. I can no more discuss Albert Hofmann’s discovery in a distanced, impersonal manner than I could write about his life and death without discussing LSD. If you would like to read a more third-person account of the life of Albert Hofmann, I recommend the entry on him in Wikipedia.

But for those of us whose lives were changed by the good doctor, it is unnecessary to explain the details of why his passing touched us. And, for the uninitiated, no accounting of the facts will clarify.

Serendipitous discovery

I learned of Hofmann’s passing on May 1 during a maypole ritual at an annual Beltane gathering. The event is a homecoming for many of us; some 500 queers, pagans, anarchists and freaks of all stripes gather on May Day to celebrate the coming of spring and all of its vernal pleasures. It is a time of celebration, for dancing all night and making love openly in the fields and forests–a time of rejoicing in the ecstasy of being alive. For many of us, it is a time to trip.

And so, when one of the elders of the Faerie tribe invoked the ancestors who had passed, and announced that at the ripe old age of 102, Albert Hofmann had died, a collective gasp shot through the circle.

It was immediately evident that most of the five hundred people gathered in a circle that day not only knew who Hofmann was, but felt a special kinship with the man. At that moment, I felt truly blessed to be in such company.

My life, like the lives of millions of others, has been irrevocably changed by Hofmann’s serendipitous discovery.

There is an almost mythical quality to his now-famous bicycle ride on April 16, 1943 when the Swiss chemist spontaneously began hallucinating after accidentally ingesting a small amount of LSD-25 that he had absorbed through his fingernails.

Sixty years later, the world is undoubtedly changed by the forces that were set in motion that day. It is undeniable that the drug has had a tremendous effect on the arts, culture, and technology of our world. While it is all but impossible to imagine the 1967 Summer of Love happening without LSD, it is equally difficult to imagine the World Wide Web (many of whose innovators were profoundly affected by the drug) without the influence of what Hofmann referred to as his “problem child.”

But LSD’s greatest contribution to humanity (and by extension Hofmann’s), was to provide an escape from the most oppressive prison of all: the gulag of the mind.

When I was 17, I tried the substance for the first time, and, like so many fellow travelers before and since, I had my perceptions of the world ripped open.

At the end of the night, the only thing I was still certain of was that reality was infinitely more complex than my normal consciousness could grasp. To this day, I know this to be true, and it is one of the pivotal understandings that have shaped the unfolding of my life.

Ask any longtime tripper what LSD has shown them and they almost invariably will tell you a story of some moment when they had an epiphany of seeing another person not as some separate object in time-space, but as a part of a continuum in which the self is enmeshed. LSD breaks down the barriers of self/other that drive the most pathological forces in our world.

I’ve often been struck by the synchronicity of Hofmann’s discovery taking place within a few years of the world’s first nuclear war. LSD has unleashed a creative force into this world as powerful as the atom bomb.

For that, all lovers of freedom, peace, and ecstatic revelry should give a hearty thanks to that noble pioneer of human consciousness, Dr. Albert Hofmann.

Note

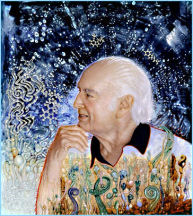

The “Portrait of Albert Hofmann” on the previous page [of the print edition] is available in an edition of 50 exemplars signed and numbered by Venosa and Hofmann. For information on prices and availability contact: roberto (at) venosa (dot) com.

Robert Venosa’s paintings are in the collections of major museums.

In addition to painting and sculpting, Venosa has done conceptual film design for the movies Dune, and Fire in the Sky, and Race for Atlantis (for IMAX). Much of Venosa’s work and attendant exploits have been published in his books, Manas Manna (Big O), Noospheres (Pomegranate Artbooks), and most recently, Illuminatus (Robert John), which features the poetic text of Terence McKenna.

His art can also be seen on numerous CD covers, including those of Santana, Kitaro, Jimi Hendrix, and others. Robert Venosa’s art can be seen at: www.venosa.com.