Is there ought we have in common with the greedy parasite,

Is there ought we have in common with the greedy parasite,

Who would lash us into serfdom and crush us with his might?

Is there anything left for us but to organize and fight?

The Union makes us strong!

—”Solidarity Forever”

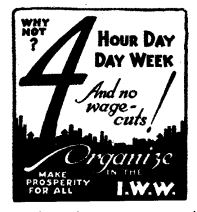

Looking back on the first century of the Industrial Workers of the World, the singing labor movement which brought us the Musician-Organizer, one can delve into its wealth of song to understand the urgency of its mission to create One Big Union that would replace wage labor and the state.

The Wobblies conceived of a world of independent workers’ councils; a belief that was one part anarchy and two parts syndicalism, but always embracing the power of song. They came to understand the strength of music as a means of expression, release and cohesion.

With little attention placed on standard administrative duties, IWW organizers focused first on traditional workers’ songs and then began writing their own. Wobbly songwriters were an integral part of organizing this union of the repressed and forgotten because music imprinted the cause on the hearts of members. IWW musicians offered songs that were mournful or proud, acerbic or sentimental.

They wrote ballads, marches, waltzes and up-tempo driving numbers that inspired solidarity as no pamphlet could. And in the folk tradition, they often wrote original, topical lyrics to popular songs of the day. By 1909 they introduced the first of many Little Red Songbooks so that all of its members might join in on the battle cry. “Sing and Fight!” became a dominant Wobbly slogan.

Even in its infancy, the IWW faced formidable challenges. As early as 1906, when Wobbly orators spoke atop soap-boxes in Spokane, Washington, they found themselves drowned out by particularly pious brass bands led by Salvation Army or Volunteers of America missionaries. Not to be outdone by the cacophony, the Spokane local soon had its own powerhouse Industrial Workers Band.

Blaring on cornets and trombones, marching to the thunderous pulse of drums and tambourines, the Wobbly band devastated all whom they crossed. The band, clad in black overalls and red work-shirts, left no corner safe for the street evangelicals. Its leader was baritone horn player, Harry “Mac” McClintock, already famed in labor circles for his compositions, “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum” and “The Big Rock Candy Mountain.”

Joe Hill (born Joel Hagglund) was the IWW’s most famous musician-activist. A well-traveled seaman, Hill immigrated to the U.S. from Sweden and soon became committed to the struggle for workers’ rights. After joining the IWW, he began organizing maritime workers, miners and others; at some point it seemed natural to bring his music into the movement. Hill could play almost any instrument, but is most often remembered playing piano in taverns or missions, and either guitar or accordion on picket lines.

Hill specialized in writing parodies with sharp literary teeth. Many were directly connected to specific organizing campaigns he was engaged in, such as, “Casey Jones, the Union Scab,” composed during the bitter 1910 strike against the Southern Pacific Railroad. Others had a more general scope, such as his most famous song, “The Preacher and the Slave.” In a parody of the hymn, “In the Sweet Bye and Bye,” Hill directed his ire at the Salvation Army preachers more concerned with the afterlife than the present one. Other Hill pieces include, “The Rebel Girl,” an early homage to Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and his anthemic, “Workers of the World, Awaken.”

The story of Joe Hill is most remembered as one of martyrdom. He survived red-baiting, police assaults and vicious Pinkerton detectives, and lived to tell of dockyard fights, barroom brawls and back-room precinct house intimidation. But he wasn’t able to survive the Utah court which found him guilty of a frame-up murder and sentenced him to death in 1915. While imprisoned, Hill wrote prolifically and toward the end offered what was arguably his most famous prose. Today it is recalled as simply, “Don’t mourn–organize.”

The year in which IWW Fellow Workers lost their Wobbly bard, they gained a true anthem, “Solidarity Forever,” composed by poet, journalist, cartoonist and songwriter, Ralph Chaplin, as he took part in a West Virginia miners’ strike. It was first published in the original IWW organ, Solidarity, several months prior to Hill’s execution, so it was surely informed by his condemned comrade’s plight. Chaplin, a Wobbly since 1913, explained that he wanted his song to be, “full of revolutionary fervor and with a chorus that was ringing and defiant.”

Its lyrics are a panoply of fiery radicalism and an unflinching denunciation of the boss’ greed. More so, it proclaimed the workers’ collective power as invincible: “In our hands is placed a power greater than their hordes of gold,” began one of its most moving verses.

Fortifying the power of “Solidarity Forever” is the revolutionary melody Chaplin used. The tune is “John Brown’s Body,” the threnody written to honor the abolitionist executed for his 1859 Harpers Ferry raid meant to encourage a slave insurrection. During the Civil War that followed, both sides of the conflict sang the song as they marched into battle–Northerners in admiration of Brown; Southerners in celebration of his death.

Ironically, following the addition of new lyrics by Julia Ward Howe in 1862, the famous melody was transformed into “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” becoming an anthem of the government that had executed Brown. By 1915, when few remembered Brown’s great sacrifice, Chaplin simply borrowed this melody for yet another revolutionary cause.

The centrality of music’s role in the Wobbly ranks was well explained in a 1918 article by writer John Reed, a strong IWW proponent. “This is the only American working class movement which sings. Tremble, then, at the IWW, for a singing movement is not to be beaten…”

Unfortunately, Reed’s prediction proved incorrect as the IWW was subjected to relentless suppression by the U.S. government, corporate goons, and local vigilantes. Still, the songs remain as does the spirit they embody. Maybe this time, Reed will be right.

John Pietaro is a labor organizer, musician and writer from New York state’s Hudson Valley. His IWW centenary CD, “I Dreamed I Heard Joe Hill Last Night: A Century of IWW Song,” is available from the IWW through its web site, iww.org.