Direct action (legal and illegal) and sabotage had been used by the U.S. and European labor movements as a method of class combat since the rise of industrialism.

Direct action (legal and illegal) and sabotage had been used by the U.S. and European labor movements as a method of class combat since the rise of industrialism.

These tactics allowed workers to fight back using whatever tools were available to them, and was viewed as a viable method of achieving worker demands outside of political channels. The IWW promoted direct action after the 1908 split with the Socialist Labor Party (which only advocated political action); however, it was not official union policy until 1914, and then only for a short time.

The word sabotage was never formally or explicitly defined, so interpretation was loose. For the most part, the IWW’s definition referred to conscious, non-violent withdrawal of efficiency, such as work slowdowns, although some probably construed a more aggressive connotation. It was strongly promoted by some, especially the anarchist IWW members in the Industrial Worker as well as in the workplace.

There is no doubt that whatever definition applied, machine breaking, slowing down, and otherwise reducing efficiency gave workers a sense of empowerment and the solidarity needed to continue their struggles. “Direct action gets the goods” was a popular saying among Wobblies.

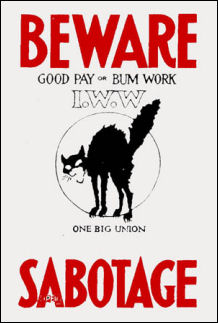

Lucy Parsons, a founding IWW member and one of the most prominent women in American labor history, was an advocate of sabotage. In one speech, she urged workers to “learn the use of explosives!” A hundred years later, police still find her fiery rhetoric offensive. A park in Chicago was recently named for her, despite clamorous objections by the local police. The IWW symbol of sabotage was and still is the black cat or “sab cat.” Originally designed by Ralph Chaplin, it was used to symbolize wildcat strikes and other forms of direct action.

The cat was recently given a facelift by Alexis Buss, the IWW General Secretary-Treasurer and is now commonly identified with the Wobblies. Union songs, poems, and cartoons, as well as printed stickers, advocate sabotage. The IWW is the only labor union in U.S. history to officially promote this tactic. That changed, however, in 1917, when the government stepped up its repression against radicals and arrested hundreds of IWW members.

Shortly before this, Frank Little and other militant Wobblies wanted to reprint Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s controversial 1913 speech to the striking Paterson silk workers, Sabotage: the Conscious Withdrawal of the Workers’ Industrial Efficiency, but in an effort to turn the government’s attention away from IWW activities, his motion was voted down. Soon after the 1918 IWW Chicago trial, the union withdrew Gurley Flynn’s and similar books and pamphlets from circulation even though the government was unable to provide any evidence of sabotage. The union also officially renounced the use of sabotage by any of its members.

By 1989, however, with almost all of the IWW old-timers gone and their jail terms no longer a harsh memory, the word appeared again on the cover of the Industrial Worker after an almost 70-year retirement.