Today, the concept of a free school has many connotations. It can mean the freedom to choose what to learn or whether to learn at all. But whatever we mean by free, we can’t really discuss the free schools of today without some background in the Modern School movement that began more than a century ago.

The Modern School or Free Education Movement, rooted in the contributions of many 19th century anarchists, would blossom with Spanish anarchist educator, Francisco Ferrer and his Escuela Moderna.

The Modern School or Free Education Movement, rooted in the contributions of many 19th century anarchists, would blossom with Spanish anarchist educator, Francisco Ferrer and his Escuela Moderna.

Rooted in competition, the old model of classical education relied on memorization by rote, the suppression of natural curiosity, and the separation of genders, with the overall emphasis on submission to authority.

In contrast, the free education system, based on principles of egalitarianism, recognized all people deserved an education, which nurtured the talents of all students, without the use of force or authority. Skills should be developed in ways stimulating to the students, through direct, multi experience with the world around them.

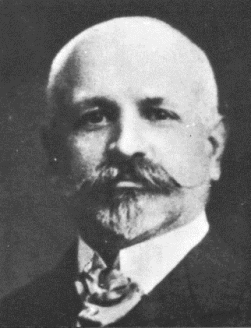

Francisco Ferrer Guardia was born near Barcelona in 1859. Though his parents were practicing Catholics, his free-thinking uncle strongly influenced him. As a young man, Ferrer’s involvement with the anticlerical, radical republican movement included an aborted attempt on the life of General Villacampe.

In France, Ferrer would refine his anarchist philosophy, devoting himself to the cause of free education. This included how open investigation and discussion could replace isolated study and examinations, which meant turning classrooms into cooperative communities rather than some competitive academia. In 1899, Ferrer married a wealthy teacher and supporter of the experimental school at Cempuis. While in Paris, Ferrer offered free Spanish lessons; one of his most notable pupils, a wealthy spinster named Jeanne Ernestine Meunier, left Ferrer a sizable fortune when she died in early 1901.

Ferrer returned to Spain later that year, now more of a threat to Spanish authorities than ever—not only as a radical reformer, but as a wealthy one, and he wasted little time putting his money towards radical reform. In September 1901, Ferrer opened the Escuela Moderna. The professed goal of the school was to educate the working class in a rational, secular, and non-coercive setting, yet the school’s high tuition soon allowed only wealthy middle class students to attend.

Ferrer planned to train a revolutionary vanguard of middle-class anarchists through his schools. Ironically, he only gained middle-class support for his schools by emphasizing the reformist aspects of his philosophy and downplaying his genuinely revolutionary aspirations. Losing sight of the importance of the working classes and their great need for free education was perhaps Ferrer’s greatest failing.

The Escuela Moderna grew rapidly. In five years, one school had grown into thirty-four. More than 1,000 students were enrolled in Escuela Moderna schools or using its textbooks, which Ferrer published himself. In April 1906, 1,700 children from anarchist and lay schools all over Barcelona assembled in a demonstration of the widening reach of free education. Unfortunately, Ferrer’s troubles would soon intensify.

That September, Mateo Moral, an employee of Ferrer’s printing house, threw a bomb at the wedding procession during King Alfonso XIII’s marriage celebration. Moral committed suicide shortly afterwards, leaving Ferrer as the government’s scapegoat. He was arrested as the mastermind of the bombing and all the anarchist schools in Barcelona were closed. Predictably, reactionary forces sprung on the chance to connect free education with political violence.

An international campaign for his release quickly developed, and Ferrer maintained his innocence. Lacking evidence to convict, the government reluctantly acquitted him in June 1907. But the damage was done. Ferrer’s moderate allies in Spain weren’t willing to be publicly connected to a suspected assassin. Many lay schools stopped using his textbooks.

In July 1909, spontaneous protests broke out in Barcelona, evolving into a general strike against the Moroccan War in what became known as the “Tragic Week.” In the course of the riots, 80 religious foundations were destroyed. The government responded by declaring martial law.

Once again, Ferrer became the scapegoat. That September, he was arrested and tried by military tribunal. Although Ferrer had very little, if anything, to do with the revolt, he was convicted as the “author and chief” of the “Tragic Week” events and was executed by firing squad in October 1909. Defiant to the end, his last words (translated) were, “Long live the Modern School!”

Known internationally, Ferrer’s execution caused an uproar throughout North America and Western Europe. Ferrer became a martyr for modern education and a key figure in Spanish anarchism.

Ferrer put free education on the (international) map, proving how it could spread through his modern schools, while helping lay the foundation for the Spanish revolution only two decades away. Subsequent schools throughout Europe and America were built on the model of the Escuela Moderna, and educators today still have much to learn from Ferrer’s contributions to free education.