Welcome to our Summer 1998 edition. Thanks to everyone who had a hand in creating our 351st issue. This issue follows our Fall 1997 edition, so please note that there was not an issue designated Winter or Spring.

As always, you can keep track of issues by noting the number in parentheses. Subscriptions expire after you have received four issues, not a calendar year. Special thanks to our Sustainers and to those who made generous donations with their subscription renewals. Also, to our writers and artists whose works grace our pages.

Apparently we gloated too soon about the imprisonment of Larry Nevers (See Fall 1997 FE). The Detroit killer cop bitterly complained about there not being enough “white people with spines!’ after two Michigan courts refused to overturn his conviction for the 1992 brutal beating death of Malice Green, a black, unemployed steelworker. Green died after receiving over a dozen blows to the head with a two-pound flashlight from the two cops after he was stopped in an inner city neighborhood.

But Nevers finally got his wish. In a decision marked by blatant favoritism and obvious racism, Reagan-appointed Federal District Judge Lawrence Zatkoff freed Nevers declaring the predominantly black jury was unduly influenced by several outside factors including watching the film “Malcolm X” during a break in testimony. Nevers’ partner, Walter Budzyn, was convicted in a second trial.

A Michigan appeals court and the state supreme court both held that the evidence against Nevers, who has a long history of brutalizing and killing black residents, was so overwhelming that viewing the film did not have a determinative effect on the jury. But outside influences appear to have had a strong effect on the judge. Zatkoff is pals with officials from the arch-conservative Macomb County Republican Party who constitute the backbone of the Nevers suburban-based defense committee.

From the moment the case was brought to Zatkoff, the fix was in. In a highly unusual move, he ordered the case assigned to him rather than select a judge by normal procedures. Zatkoff sped the case through the docket three times faster than usual and presented an 88-page decision only 11 days after the prosecution’s answer, minutes before the close of court for the New Years’ holiday. It seems clear the judge wrote his brief prior to hearing the arguments.

Zatkoff took off his black robe and donned a white one to join the lynch mob who are horrified that a cop, even one with a brutal history, can be punished for killing an African-American. You can hear the racist mentality of Never’s supporters on local right-wing talk radio as they vehemently denounce Malice Green as a “crack-head” and “low-life,” as if this alone is grounds for execution at the hands of a cop death squad.

There’s a homemade memorial at the corner of Warren Ave. and 23rd where Nevers bludgeoned the small, unresisting Green to death by 14 blows to the head with his two-pound flashlight. People from all over come to pay their respects to a man considered a martyr by many in the community. They know Malice Green was not the first black person to die at the hands of racist cops, and they’re afraid he won’t be the last.

The centerpiece of the memorial is a mural painted on the side of an abandoned building by local artist Bennie White Ethiopia depicting a christ-like Green. Two days after Nevers was welcomed home from four years in a Texas federal pen, someone vandalized the painting with a swastika and the words, “Nevers Rules.”

While Ethiopia quickly repaired the damage, the killer and his friends, all “white people with spines,” were celebrating Judge Zatkoff’s decision.

A Wayne County Circuit Court jury hearing the retrial of fired cop Walter Budzyn brought in a verdict of guilty of involuntary manslaughter, March 9, for his role in the beating death of Malice Green. Although convicted on a lesser charge then the original one of second degree murder, this second trial cut the ground out from under the racist contention that the two cops were victims of reverse racism by a vengeful, predominately African-American jury.

Following Budzyn’s conviction, racist state legislators abolished Detroit’s 135-year-old mostly black city court system in retaliation for its effrontery of convicting Nevers and Budzyn.

However, the beating death of Green was so egregious, that the predominately white county jury also brought in a verdict clearly condemning Budzyn.

When retired Detroit Mayor Coleman Young died of emphysema at age 78 last winter, he was buried with ceremonies fit for a pharaoh.

Young held office from 1974 to 1993, an era when Detroit cemented its identity as ground zero of the rust belt. After forty years of flight by the auto-makers, other manufacturers and hundreds of thousands of residents, the once heralded “Arsenal of Democracy” by the end of Young’s reign had the highest poverty rate in urban America and was scruffy testimony to the false promise of industrial capitalism.

A flamboyant, witty, charming despot, tremendously corrupted by the trappings of power, Young cruised the city in an armor-plated limousine, surrounded by Uzi-toting guards. His lifestyle combined the proclivities of Howard Hughes and Hugh Hefner.

Young sometimes holed up in his city-owned mansion on the Detroit River for weeks at a time, sleeping by day, playing solitaire dressed in pajamas by night in front of a glowing, big-screen TV. He dated women who worked for him, and fathered a child when he was 64 with the 34-year-old assistant director of the Department of Public Works.

With the city 80 percent black and the suburbs 90 percent white, metro Detroit is one of the nation’s most segregated areas. Young was a polarizing figure. Black Detroiters generally admired him for his outspoken civil rights activism in his younger days and for attempting, in his own way as mayor, to rebuild Detroit, which had lost 400,000 residents in the twenty years before he took office. More than 90,000 people filed past his casket during the two days it was on view, and thousands more lined the route of his funeral procession, some of them waving or giving his passing hearse the black-power salute.

Whites largely despised Young, blaming him for capital’s massive economic looting and abandonment of the central city, and because he was pugnacious and direct in challenging suburban racism. The level of irrational hatred against Young by whites was breathtaking. Racist comments and jokes were common, and few seemed to understand why black Detroiters reacted so emotionally to his passing.

While Young was provocative in discussing race, he was not above using it to advance his career. He assailed anyone who dared to oppose him as an “Uncle Tom,” and once called an opponent whom he had accused of catering to whites—”an important first in American politics—a black white hope.” Local community activists, for example people who fought the Detroit trash incinerator (aptly dubbed “Coleman’s Cathedral”), typically found themselves taunted by Young and his machine’s footsoldiers to go back to the suburbs.

Young came out of the labor movement, and FBI files indicate he was followed, harassed and blacklisted for his radical activities before World War II. In 1952, the House Committee on Un-American Activities summoned him to discuss Communism among black union militants. “You have me mixed up with a stool pigeon,” Young told the committee, which had ruined the reputations of countless people in its search for fellow travelers. Young boldly defied committee members, some of them Southerners, lecturing them on the proper pronunciation of “Negro” and refusing to answer their questions. “I am fighting against un-American activities such as lynchings and denial of the vote,” Young declared.

Young’s daring effrontery to the Congressional witch hunters was so admired in the African-American community that his testimony was released on a 78 rpm record and became a fast seller in the city’s Black Bottom district.

Young’s main method of resuscitating Detroit was to hand over tax breaks to wealthy corporations to build something, anything, to replace decrepit factories and homes left behind during decades of white flight.

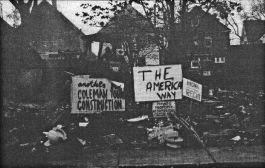

His most memorable project was to level Poletown, a neighborhood of 3,400 working-class residents and hundreds of homes, shops and institutions, to make room for a General Motors luxury car plant.

It was one of the largest, fastest and most brutal urban renewals in American history. The irony of a former radical destroying peoples’ homes for the world’s largest corporation was not lost on everybody. But the spectacle of a proud black man begging white-run firms for a few measly crumbs was representative of the ultimate tragedy of Coleman Young.

This year marks three decades since the publication of the late John Hersey’s The Algiers Motel Incident. Hersey, the acclaimed author of popular books such as Hiroshima and A Bell for Adano, came to Detroit shortly after the 1967 rebellion, so his investigation into the execution-style murders of three young African-American men in a sleazy motel attracted considerable attention.

To mark the anniversary, the John Hopkins University Press has reissued the book, coincidentally just in time for Walter Budzyn’s retrial and conviction.

In the rebellion, 43 people died and 7,000 were arrested; it took the combined forces of police, state troopers, National Guard troops and the U.S. Army nearly a week to restore “order.” Hersey’s book focused on events at the Algiers Motel on July 26. Police and national guard troops raided the motel, ostensibly to hunt for snipers, though no guns were found.

Inside, they lined up seven black men and two white women along a wall, stripping the women and viciously beating the men. The cops took the guests one by one into a room, and when the night was over, three of the men had been shot dead as they assumed what the medical examiner termed “nonaggressive postures.” The three white cops charged in the massacre were brought to an up-state venue tried by an all white jury and acquitted.

While readers may differ with Hersey’s assertions that racism derives from the minds of people and not necessarily from a haywire social-economic system, the book is a fiery trip back in time, and questions who was really rioting during the tumultuous week the Motor City burned.