In March of this year a small article appeared in the Detroit Free Press announcing the last public hearing before the City of Detroit was to begin building the world’s largest trash-to-energy waste-incinerator plant. For those of us who live in the Cass Corridor/Wayne State University area, within a mile of the proposed plant’s location, the city’s plans came as one more horror in a long list of direct assaults on our lives.

For a few of our friends, the proposed plant was the final straw and brought home in a visceral way all that they felt was wrong with this world—brought it literally home to our own neighborhood.

For a few of our friends, the proposed plant was the final straw and brought home in a visceral way all that they felt was wrong with this world—brought it literally home to our own neighborhood.

A handful of community residents made the trek to the state capital in Lansing, some 90 miles away, to confront the politicians and corporate stooges who stood behind this monstrous plan.

Thus began an intense effort by a loose coalition of friends, neighbors and others who have tried to stop the construction of this plant. Our efforts led a number of us to plunge ourselves into studying the technical aspects of “waste management,” “risk assessment” and other terms so casually bantered about by the so-called experts in the field.

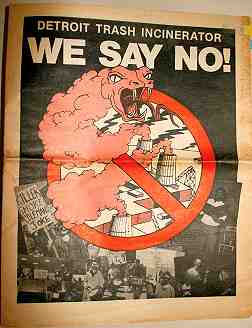

In less than a week we researched, wrote, and printed our own tabloid newspaper detailing our opposition to the politicians’ plans to poison us all. Thousands of leaflets were distributed; three demonstrations took place, and some 500 angry people appeared at a public meeting at city hall to confront city and state officials.

Complex Technological Questions

From the beginning, the complex technical questions that we were forced to master tended to muddle the underlying significance of the plant construction. For example, such incinerator plants were originally touted as technological solutions to the crisis caused by landfilling the immense amounts of garbage produced by industrial capitalism and the resultant contamination of water and air by the toxins which leak from dumps. City officials contend that the City will run out of land-fill space within a decade. These arguments convinced even established environmental groups nationally and locally to support incineration as the “lesser evil.”

The credibility of these arguments began to unravel when it was revealed that state environmental officials had made a thousandfold calculation error in assessing the pollutants released and the subsequent cancer risks to the population. This forced the State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to recommend “state of the art” pollution control devices which would somewhat reduce the level of pollutants released into the air. At a raucous public hearing held in Detroit’s City-County Building in early April, the DNR recommended such pollution control devices as “baghouses” (a teflon-coated fabric filter produced; ironically, by chemical corporations such as Dow) and “acid scrubbers” (de-acidifying lime sprayers in the smokestacks).

The City packed the chambers with city employees being paid overtime and barred the doors to over a hundred residents, while state and city officials and consultants droned on for over five hours, all the time denying those present a chance to speak. The city and its paid liars denied the public would be in any danger. (At one point City Finance Director Bella Marshall, in a demeanor combining that of a sadistic dominatrix and an armored robot, chastised the crowd for heckling and for such creative signs as “Burn Politicians, Not Plastic,” and reassured angry residents, saying, “I know you’re all wondering what [plant emissions] will do to my car, what will they do to me. We’re here to answer your questions.”) “Expert” consultants brought in by the City from Weston Engineering performed their tricks well, pronouncing (after a litany of juggled statistics and false criteria) living in the shadow of the plant “safer than eating a peanut butter sandwich.” At 3:30 a.m., when most people had already left in disgust, the Air Pollution Control commission voted to go ahead with the plant even without the baghouse and scrubbers.

Clean Burn?

While liberal conservationists argued for the “more advanced” controls and even handed out polyvinyl stickers saying “Clean Burn,” most local residents didn’t want to see the incinerator built in any form. As we argued from the start, these incinerators are deadly no matter what pollution controls are used. The lethal heavy metal vapors, acids and assorted toxins they emit include cadmium, mercury, arsenic, lead, hydrochloric acid, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Particularly devastating is the release of the highly toxic chemicals in the dioxin and furan families—chemicals which led to the evacuation and permanent abandonment of Seveso, Italy in 1976, and Times Beach, Missouri in 1983.

Without the pollution controls, in one year the plant would release twenty million pounds of pollutants—the largest percentage made up of acids and fly-ash. But even with the controls, 1.5 million pounds of hydrochloric acid and three million pounds of all other toxins would escape annually. Neither proposed design would stop the release of heavy metal vapors, dioxin and furans—the most deadly of the pollutants. And though incineration has been presented as an alternative to land-fill, about thirty per cent of the waste would remain as deadly ash and would have to go—you guessed it—to a land-fill, and the ash collected by the bag-houses would be so toxic that it would have to be dumped in special toxic waste landfills along with the bag fabric worn out by the acids.

The whole argument for control devices suggests that the production of a world of toxic garbage is manageable and negates the necessity for the abolition of industrial capitalism in its entirety. As one friend wrote in the tabloid we published, “We are presented with an illusory layer of options that essentially says, ‘Choose your toxin.'”

The Business of Business

Of course, big city politicians aren’t in the business of addressing the tremendous problems brought about by commodity capitalism and industrial production, they are in the business of business, and trash-to-energy is big business. To divert people’s attention from the dangers of incineration, the city administration of Mayor Coleman Young attacked incinerator opponents as white environmentalists from the suburbs out to stir up problems for Young’s mostly black administration. The city patronage machine was mobilized to keep block clubs, neighborhood associations and black churches (the core of his support) from stepping out of line.

The mayor continued to railroad the project through even as it was revealed by the local press that the firm contracted to build this $470 million incinerator, Combustion Engineering, also has a major contract with the South African government to build power plants there—a direct affront to a mostly black city, and essentially a violation of the city’s own antiapartheid investment ordinances. But Young isn’t in the business of opposing apartheid, despite his symbolic (and comfortable) arrest last year at the South African embassy in Washington D.C., he is in the business of serving business. The plant he is promoting will lead to the deterioration of health and to uncounted deaths of people in this mostly black city, so who would expect him to really take an interest in the welfare of black people in Africa?

A Radical Edge

The movement to oppose the incinerator provided a unique opportunity for those in our community who share an anti-authoritarian vision. As it happened, we were among the first to disseminate information opposing the construction of the plant. While traditional liberal environmental groups like the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society continued in their efforts to lobby politicians and to submit to proper procedure, we chose to publicize and agitate on a wider scale.

Rather than get bogged down in arguing how many deaths per million were “acceptable,” we raised questions about the very production of plastics (the source of dioxins) and about the self-destructive throwaway attitude of this society. While the leadership of the environmental groups tried to appear “realistic” and responsible, not demanding what capital deems to be impossible, we chose to address the political question of the capitalist megamachine and industrial society.

The involvement of those willing to raise these questions lent a radical edge to the widespread opposition to the incinerator. It was encouraging to see some of the members of local environmental organizations break through their demoralization brought on by years of realpolitik and start to think once more about deeper issues. At one point, both the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society changed their position, dropped their demand for pollution controls, and came out against the incinerator in any form.

However, it appears that the leaders of both organizations have become uncomfortable working with those who hold a more radical critique or with any community which wants to act autonomously as an equal, for that matter. In an effort to regain their position of respectability the two environmental organizations flew in their own experts and held a meeting “for invitation only” with the politicians and the press. Cass Corridor residents were discouraged from attending. The meeting turned out to be rather poorly attended even by those for whom it was intended.

Now that the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has stepped in and may possibly force the city to add the pollution controls, there is the danger that these groups will retreat to their previous position, the state will pick up the difference, the plant will be built with the control technology, and we’ll be poisoned.

For those who initiated much of the anti-incinerator activity, this experience raised many questions about the nature of organization. Due to our heavy involvement, we felt the pressure to become the leaders of some sort of broad-based coalition against the incinerator. To be “effective” in trying to stop the plant, some argued, meant working with lawyers, the news media, church groups and sympathetic politicians. It pressured us to moderate our politics and focus our attention on a single goal, stopping the plant.

Needless to say, most of us felt less than comfortable being thrust into this role. There was a marked difference between the exhilaration we felt in the early weeks when we feverishly worked with close friends who shared similar views and the later period when the incinerator opposition had moved into the realm of open public meetings. The larger group lacked the sense of trust and the shared perspectives of our informal affinity group; inevitable conflicts arose. Some of us became discouraged and we did not satisfactorily solve the problems posed by working with people whose views we did not share.

Process of Radicalization

This remains a problem which anti-authoritarians must grapple with in order to work effectively with others in our neighborhoods and workplaces. First of all, we have to find the means to translate our political beliefs into action, particularly when we are faced with a direct attack on life like Detroit’s incinerator. Secondly, we should not underestimate the political process of radicalization which often accompanies a person’s involvement in what appears to be a single issue. An issue like garbage incineration can ultimately lead to an entire critique of society, depending on people’s willingness to uncover the hidden connections between seemingly unrelated aspects of our lives. Every social struggle holds the potential for becoming a battle against the modern technological society as a whole.

In that sense, despite setbacks, we still feel positive about our involvement in this fight. While we are a long way from stopping the incinerator, we have to some degree been able to participate in creating a context in which the entire question of life today could begin to emerge. With very limited resources, we reached people throughout the city and helped make them aware of a horrendous project that the City wanted kept quiet. Along with other opponents of the plant, we were labelled “environmental terrorists” by the arch- reactionary Rambo gazette, the Detroit News, and an obviously nervous city administration responded to our symbolic gesture of planting a maple sapling at the site by handing out tiny seedlings to the honchos present at the groundbreaking ceremony while cops kept demonstrators at bay a few blocks away.

While we haven’t stopped the incinerator, it hasn’t been built yet either. Incinerators have even been built in other cities only to be closed down within weeks of starting operation, and some countries, such as Sweden, have imposed moratoria on such plants. As the horrors of petrochemical civilization loom larger every day, people are beginning to realize that it will take far more than lobbying politicians and begging for favors from the powerful to stop this project and others like it. But it can be done—and people are increasingly aware of what it will take to do it: a direct confrontation with industrial society and its power structure, and a vision of a different way of life based on being, not having.

This was what we had in mind when we planted the maple tree. The corporate technocrats and city politicians fenced in our little sapling and promised to replant it near their incinerator. Our task is to find a way to replant all of them, so that many more saplings like ours can thrive, so that we can too.