This article is the second in a series of counter-Bicentennial pieces dealing with the more sordid and less-acknowledged incidents in America’s 200-year-old history.

The Massacre

March 16, 1968, My Lai 4, Quang Ngai Province, 7:30 A.M. Under direct orders from Lieutenant Colonel Frank A. Barker Jr., command leader of assault unit Task Force Barker, nine troop-transporting helicopters preceded by two gunships enter the My Lai area.

At 7:35, Charlie Company registers its first Viet Cong “hit”–an old man gunned down after jumping from a hole and waving his arms frantically in stark terror.

Three platoons advance into the peaceful hamlet. the first two immediately and the third soon after. The villagers–women, children and old men–take little notice and continue cooking their breakfast rice over outdoor fires. There is no sniper fire. No Viet Cong are sighted. The first platoon begins to round up villagers.

Without warning, and without provocation, a young member of the platoon suddenly grabs a civilian and plunges his bayonet into the man’s back. Another thrust of the bayonet finishes the villager off. The same G.I. then pulls a 40-50 year-old man from the crowd and pushes him backwards down a well shaft, an M26 grenade, pin pulled, following close behind.

Soldiers pass a group of children and old women kneeling and praying around a small temple and methodically execute them one-by-one with a bullet in the head. Urged to “waste” the hamlet by its superiors, the platoon fires on any and all Vietnamese in sight.

The second platoon to the north begins to ransack the huts, gun down the occupants huddled inside, slaughter the livestock and ravage the crops.

The third platoon enters the hamlet. Terror-stricken villagers toting personal possessions in handmade wicker baskets attempt to flee, only to be cut in half by fire from the helicopter gunships.

“Kill everyone,” orders Captain Ernest L. Medina. “Leave no one standing.” There are few objections from his men.

An old woman is knocked down and shot pointblank with an M16 rifle. A group of men, women and children are machine gunned on command. Villagers run into bunkers built for protection from enemy attack. When the bunkers are full, grenades are lobbed into them. A woman carrying a baby in her arms walks from her hut weeping and is shot down. The G.I. opens up on the infant as well. An officer seizes a woman by the hair and blows her brains out with his.45 caliber pistol.

One G.I. chases a duck with a knife while another is butchering a cow with his bayonet. A third G.I. borrows someone’s M79 grenade launcher and fires at a water buffalo from can’t-miss range. “I hit that sucker right in the head; went down like a shot,” he boasts. “You don’t get to shoot water buffalo with an M79 every day.”

By 8:40, My Lai is in ruins. Two large groups of civilians have already been annihilated. Wells are fouled, livestock destroyed and foodstock strewn everywhere. Anything burnable is aflame.

“Push all those people in the ditch,” Lieutenant William E. Calley Jr.- orders his platoon. Calley begins shooting into the pit and others follow, some switching from automatic-fire to single shot to conserve ammunition. Machine guns strafe the crowd. A grenade or two is tossed in for good measure. Miraculously, a two-year-old boy emerges crying, but some how unhurt. As he runs toward the hamlet Calley grabs him, throws him back into the bloody ditch and shoots him, making sure not to miss this time.

The carnage goes on, interrupted only by periodic cigarette breaks. A 13-year-old girl is savagely raped and murdered. A baby desperately tearing at its mother’s blouse to nurse is hacked to pieces by bayonet-wielding G.I.’s. A 3-4- year-old boy searching for his family amidst a pile of bullet-riddled bodies is torn apart by M16 fire. The impact jolts the body backward atop the pile.

By noon the platoons begin pulling out, the village left behind a fiery, foul-smelling plundered inferno.

“We met no resistance and I only saw three captured weapons,” Michael Bernhardt, a member of Charlie Company, later recalled. “We met no casualties. It was just like any other Vietnamese village–old papa-sans, women and kids. As a matter of fact, I don’t remember seeing one military-age male in the entire place, dead or alive. The only prisoner I saw was in his fifties.”

By nightfall the Viet Cong returned to My Lai 4 to help the survivors bury their dead. The burial took five days. Nguyen Bat, a survivor, remembered that, although few of the villagers were VC before the massacre, “After the shooting all the villagers became communists.”

The report from Charlie Company to the Pentagon on the evening of March 16 noted initial “contact with the enemy force” and reported a body count of 128 with three enemy weapons captured. A year-and-a-half later, Army investigators discovered mass graves at three sites and estimated that between 450 and 500 people, mostly women, children and old men, had been killed there.

What is less known is that just down the road from My Lai 4, one-and-a-half miles to the west in a hamlet named My Khe 4, 90 or more civilians were murdered in the same brutal fashion by members of Bravo Compang, another faction of the Army’s 11th Brigade. The village was then destroyed in a manner similar to that of My Lai.

The Cover-Up

The My Lai 4 cover-up was begun almost immediately by Lieutenant Colonel Barker, the commander of the three-company, 500-man task force which bore his name.

Barker took four initial and crucial steps in obscuring the events which had taken place at My Lai: he persuaded his artillery liaison officer to accept unquestionably the report that artillery had killed 69 Viet Cong; he assured helicopter commander Major Frederic W. Watke that the complaint of helicopter pilot Hugh C. Thompson Jr., who rescued Vietnamese villagers from his fellow soldiers at My Lai, concerning the slaughter was unwarranted; he urged the distortion of a news story to be written and sent to the States for nation-wide publication; and he prevented Captain Ernest Medina from returning to the village to provide an accurate body count.

At the same time, there were abortive attempts by members of the 123rd Aviation Battalion to bring some truth about My Lai to the attention of higher authorities. Although reports stating that civilians were, in fact, killed at My Lai were filed at both the division air office and its intelligence office, they could not be found at a later date.

On the day after the massacre, General George M. Young surveyed the My Lai site by air, beginning an investigation as ordered by his superior, Major Samuel W. Koster, the commanding general of the American Division of independent infantry units. Word of the civilian casualties had spread and a follow-up report was now imperative.

Young returned obviously disturbed by what he referred to as “improper conduct” on the part of Charlie Company and called a high-level meeting for the following morning with Colonel Oran Henderson, commander of the 11th Infantry Brigade, Lieutenant Colonels Barker and John L. Holladay and Major Watke. The result of the meeting was that Henderson was instructed to investigate and file an oral report as to what he found.

While Henderson did follow through with his investigation, listening to testimonies from Ernest Medina and accusing pilot Hugh Thompson among others, he also accepted every denial at face value. As requested, he made his report to Koster and Young, then wrote his whitewashed version of the massacre and filed it away. By the end of 1969, the report had disappeared from the files along with other information on My Lai.

Three days after the mass murders in My Lai 4 and My Khe 4, the South Vietnamese government had the details, chiefly from talking to the survivors, what few there were.

Although the Thieu government showed little interest in investigating or making public the alleged atrocities–mainly because the Census Grievance Committee, an organization set up to hear complaints against the Saigon government, was covertly financed by the C.I.A.–the National Liberation Front in Quang Ngai did. Three-page leaflets filled with surprisingly accurate details were distributed in the province within days, creating even more uneasy feelings amongst the U.S. military and Saigon governments. The Thieu government attempted to dismiss the leaflets as V.C. propaganda, but the Vietnamese people knew better.

By mid-April Radio Hanoi was broadcasting word of the massacres. The broadcasts were translated, reprinted and published in the daily Foreign Broadcast Information Survey, a compilation of world-wide radio broadcasts published by the C.I.A. and made available to government agencies and newspapers in America and around the world, yet they were virtually ignored in the States.

The Uncovering

Had it not been for Ronald Ridenhour, a 22-year-old ex-G.I. from Phoenix, the My Lai massacre may never have been made public.

As a former helicopter door gunner in Vietnam, Ridenhour had observed the massacre site from the air a few days after the attack and had seen the destruction first hand. Outraged at what he’d seen, he vowed that at some point in time once he’d left the service, he’d see that those involved would not get away with their awful deeds free and clear. In March, 1969, with the aid and advice of a former high school instructor, he did just that.

After composing a letter describing the My Lai massacre from what he’d witnessed and pieced together from talking to some of the men involved, Ridenhour made thirty copies and mailed them out. By registered mail, letters were sent to President Nixon (nine to Nixon), Eugene McCarthy, J.W. Fulbright, Edward Kennedy (the three leading anti-war spokesmen in Congress), and five members of the Arizona Congressional delegation including Barry Goldwater and Morris Udall.

By ordinary mail, letters were also sent to the Pentagon, the State Department, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, thirteen other members of the Senate, three members of the House, including Armed Services Committee Chairman L. Mendel Rivers, and to the House and Senate chaplains.

Although the majority of the letters were never acknowledged, Representatives Morris Udall and L. Mendel Rivers took a special interest in what Ridenhour had to say. The two wrote a letter to Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird suggesting further investigation of the matter.

Laird forwarded the letter to the Army, which had received six other Congressional referrals concerning Ridenhour’s allegation. Clearly this was something which couldn’t easily be swept under the carpet and forgotten.

On April 12, Ridenhour received a letter from the Army Chief of Staff’s office advising him that My Lai was now under “proper investigation” and thanking him for bringing the matter to their attention.

Meanwhile, the Army turned the investigation over to Colonel William Vickers Wilson of the office of the Inspector General and directed that a full-scale inquiry be made. Operating quietly, Wilson made his way across the country talking to, among others, Ridenhour and former members of Charlie Company in Vietnam.

On June 13, 1969, a major breakthrough was made. At the Inspector General’s office of the Army in Washington, a line-up was held in order to enable key witness Hugh Thompson of the 123rd Aviation Battalion to identify the officer responsible for directing operations at the drainage ditch in My Lai. In the line-up was Lieutenant William Calley. Thompson picked Calley out with little trouble and also fingered Medina as the other officer involved in the shootings.

While Wilson was conducting his investigation, Ridenhour was being kept in the dark, warned against leaking any of what he knew to the press. It had been over five weeks since he’d heard any news and he was growing impatient, eager to know whether his allegations were going to be heard or buried.

By the end of July, Wilson had completed interviews with thirty-six witnesses, including 11th Brigade Commander Colonel Henderson. Evidence against Calley was growing and General Westmoreland ordered the Inspector General’s office to turn over the results of the investigation to the Provost Marshall’s office of the Army and its Criminal Investigation Division to determine whether criminal charges could be filed.

Realizing that military proceedings would have to be filed against Calley to protect its own reputation, the Army formally preferred charges, accusing him of six specifications of premeditated murder on September 5, one day before Calley was set to leave the service.

The first public word of the My Lai massacre came in the form of a short news release from the public information office at Fort Benning to the Georgia press on September 5. Five days later, the Huntley-Brinkly evening news program made mention of Calley’s arrest. Little more was said for awhile.

Ridenhour, by now convinced that Calley would be used as a scapegoat by the Army while high-ranking officers would get off without a reprimand, decided to take the matter into his own hands. Tired of waiting for something to happen, Ridenhour gave his file on My Lai to Ben Cole, a Washington reporter for the Phoenix Republic, a local daily newspaper.

Although Cole never did research and write the story, other newsmen did, including Seymour Hersh of the New York Times. Predictably, once the Times picked up the story, other dailies did as well, as did weekly news magazines.

Seven months after Ridenhour had mailed out his thirty letters, Army Secretary Stanley R. Resor and General Westmoreland announced the formation of a panel headed by Lieutenant General William R. Peers to explore “the nature and scope” of the original Army investigations. The Peers Panel began its investigation on November 24, 1969, and completed its hearings 398 witnesses later in early March 1970.

Amongst its findings, the Panel heard testimony which uncovered the My Khe 4 massacre of March 16, 1968. As a result, it was forced to broaden its investigation to include the entire Son My area of the Quang Ngai Province.

On February 10, 1970, Captain Thomas Willingham, platoon leader of Bravo Company, was formally charged by the Army with the unpremeditated murder of twenty Vietnamese civilians. As with Calley, the charges were issued at the last minute in order to assure the military of jurisdiction.

Finally, on March 17, charges were formally filed against fourteen officers. Among the noteworthy were: Major General Samuel Koster (failure to obey lawful regulations and dereliction of duty): Brigadier General George Young (failing to obey regulations and dereliction of duty); Colonel Oran Henderson (dereliction, failing to obey regulations, making a false official statement and false swearing); Major Frederic Watke (failing to obey regulations and dereliction); Captain–then Lieutenant–Thomas Willingham (making false official statements and failing to report a felony, in addition to unpremeditated murder); and Captain Ernest Medina (murder and failing to report a felony).

Two weeks late the cover-up charges against Medina were dismissed. Two months after that, the Third Army dropped the murder and cover-up charges against Willingham.

In June, cover-up charges were dismissed against Young and two other officers. By January, 1971, charges were also dropped against Koster, Watke and three others, although there was admittedly some evidence that Koster had known about the deaths of 20 civilians. Koster was later demoted to a brigadier general and stripped of a Distinguished Service Medal.

When the dust had settled, only one officer of the fourteen was required to face a court-martial, Colonel Oran Henderson. Calley had been charged earlier before the Army’s decision to consolidate the criminal cases at Fort Benning, Georgia.

On December 17, 1971, Henderson was found not guilty of the cover-up charges. Ronald Ridenhour’s prediction had come true. Only Calley was convicted, and even he was later freed upon order from President Nixon.

As Seymour Hersh pointed out in his books on the My Lai and My Khe massacres, “No attempt was made in the final Volume I report (of the Peers Panel) to deal with the continuing and more substantial issues raised by My Lai 4 and My Khe 4: the military attitudes; the caliber of officers; the training techniques; the promotion system–these and other factors basic to the Army itself.”

The sole recommendation, Hersh goes on to point out, was that “Consideration (should) be given to the modification of applicable policies, directives, and training standards in order to correct the apparent deficiencies noted above.” There’s never been any indication that the recommendation was ever implemented.

Why My Lai 4?

To millions of people all across the nation and the world, the news of the My Lai massacre was shocking, disgusting and downright incredible. Yet to the American fighting men in Vietnam, My Lai wasn’t even anything new, except perhaps for its proportions. Mass murder in the hamlets and rice paddies of Vietnam was all but an everyday occurrence.

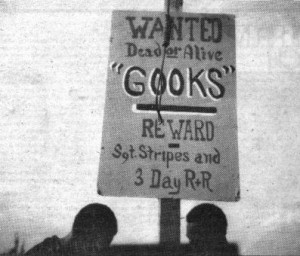

Behind all the bloodshed wreaked upon the Vietnamese people was basically a vicious racist attitude on the part of the American military. To the military, the Vietnamese weren’t even human. They were those small, yellow-skinned “gooks” or “clinks” or “slopes” who stood in the way of a glorious American victory.

A perfect example of the military’s total disregard for the Vietnamese lies in the minimal education it provided its own men there. G.I.’s in Vietnam were given only two hours of instruction a year in the rights of prisoners, plus wallet-sized cards on which were printed “Always treat your prisoners humanely.” Knowledge as to Vietnamese customs, values and traditions was almost nil.

The American military’s bloodthirsty attitude towards the Vietnamese ran from the top to the bottom. One of the worst at the top was George S. Patton III, the commander of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment south of Quang Ngai. Amongst his more memorable quotes are: “I do like to see the arms and legs fly,” and “The present ratio of 90 percent killings to 10 percent pacification is just about right.”

There was no soft spot in Patton’s heart. For Christmas, 1968, he mailed out cards reading “From Colonel and Mrs. George S. Patton III–Peace on Earth” with color photographs of dismembered Viet Cong soldiers stacked in a pile.

At the bottom, at G.I. level, the attitude was no better. One of the favorite jokes circulating around Quang Ngai was that the loyal Vietnamese should be put out to sea in a raft. Everybody left in the country should then be killed and the country paved over with concrete. Then the raft should be sunk.

As for why a massacre at My Lai 4 specifically, an explanation has to begin with some historical perspective. The people of the Quang Ngai Province have a history of rebellion going back to the 16th Century and covering periods such as the Vietminh revolts against the French in the 1930s and as Viet Cong against the Saigon government in the ’50’s and ’60’s. By the mid-60’s Quang Ngai’s Province was South Vietnam’s third largest. It was also considered the toughest Viet Cong stronghold.

Naturally, when the United States entered the war the Quang Ngai Province became its first objective. Quoting Mao Tse-tung, the American military remarked that in guerrilla warfare the guerrillas are the fish and the people the water and the only way to catch the fish would be by removing the water. Yet, despite all its efforts, Quang Ngai was still heavily VC in the spring of 1967.

In September 1967, the Americal Division was formed composed of three brigades under the command of Major General Samuel Koster. Hardly a crack fighting force, the Division nevertheless was highly competitive. Competition for body counts and battle ribbons was high. The desire for combat was so strong amongst the field grade officers that command experience was forced to be limited to six months.

Charlie Company, under the command of Ernest Medina, was no exception. The unit was made up of men impatient for combat. When none came its way, it made its own by pushing around Vietnamese Civilians and eventually torturing and murdering them.

When given the My Lai assignment, the men of Charlie Company reacted accordingly. Some of the men involved later recalled that Medina ordered them to “kill everything in the village” and to leave it in such a condition that “nothing would be walking, growing or crawling.” For many in Charlie Company, the My Lai massacre served as a relief-bringing catharsis.

For Ron Grzesik of Charlie Company, My Lai 4 was the end of a vicious circle: “It was like going from one step to another, worse one. First, you’d stop the people, question them and let them go. Second, you’d stop the people, beat up an old man, and let them go. Third, you’d stop the people, beat up an old man, and then shoot him. Fourth, you go in and wipe out a village.”

For further information, read Seymour Hersh’s two books on this subject: My Lai 4 and Cover Up; Random House, 1970 and 1972 respectively.