EDITORS NOTE: The following speech was given to a meeting of the Detroit Circle held November 21 in the McGregor Memorial Building. Dr. Pollack is a History professor at Wayne and long active in the movement protesting the war in Vietnam.

Perhaps the biggest mistake many of us make when speaking about Vietnam is that we focus only on Vietnam, and in doing so, engage in a debate with the forces supporting the Administration on their own ground. Not that a case against the war could not be made even there, for it could. But I think the time has come to enlarge the inquiry and to make a case not simply against the war, but against the structure of American society which makes that war possible in the first place. Why are we in Vietnam? Until we dig deeply into that question and explore all the ins and outs, we will be forced to remain on a superficial level and to confront the war as a single issue–and in thinking of the war as a single issue. when and if this war is resolved, then the basis for the criticism is removed. This is not as it should be. I urge you to consider that the Vietnam war, as important as it is, is only a symptom–only a symptom of the larger course American society is pursuing. And one does not accomplish very much by confronting symptoms when the underlying causes remain unhampered.

I suggest that we are in Vietnam for a number of reasons, all of which converge on a central point: We are at war today because we cannot–or will not solve the internal problems at home. This war has, as in numerous other societies, served as a diversion, taking our minds off the need for basic changes–and the failure of domestic policies even to solve the most glaring defects signify this need–in such crucial areas as civil rights, jobs, the eradication of poverty, urban ghettos and an absurdly inadequate and qualitatively poor system of public education. Make no mistake, the society is in bad shape, and the war in Vietnam is one means of obscuring that fact from ourselves–both directly, by making a significant contribution to propping up a faltering economy.

I suggest that we are in Vietnam for a number of reasons, all of which converge on a central point: We are at war today because we cannot–or will not solve the internal problems at home. This war has, as in numerous other societies, served as a diversion, taking our minds off the need for basic changes–and the failure of domestic policies even to solve the most glaring defects signify this need–in such crucial areas as civil rights, jobs, the eradication of poverty, urban ghettos and an absurdly inadequate and qualitatively poor system of public education. Make no mistake, the society is in bad shape, and the war in Vietnam is one means of obscuring that fact from ourselves–both directly, by making a significant contribution to propping up a faltering economy.

It would, I think, be a mistake to label the war as an imperialistic venture–at least as we generally understand the term–in which the United States is protecting or establishing investments in Vietnam. Of course, there is some of that going on, But that should not sidetrack us from a larger point, and an economic one at that. I suggest that when administration supporters nervously shake off the notion that we have an economic gain at stake in Vietnam, that we remind them the gain is a very real one, indeed it is one that makes the difference between chronic unemployment, a severe recession and the possibility of internal turmoil at home on one hand, and the kind of shaky prosperity that we now have in which the working class has been silenced and bought off on the other. The war in Vietnam is keeping the economy going, and you don’t need a Marxist to tell you this. Just pick up the latest issue of Fortune magazine where it discusses how large war orders have not only given confidence to the stock market, but have brought about the use of productive facilities that would be in trouble otherwise. We now have at least five million unemployed anyway, and this with a defense establishment running over $fifty billion. Is there any doubt as to what shape our economy would be in if we took away that $fifty billion?

But you may ask, why take it away? Why not put it into the much needed education and health programs, rebuilding our cities, doing something about poverty, etc.? The question is a good one, and it brings to me another important point. Namely, suggest that defense monies will NOT go into social welfare so long as American society remains the society as we know it today. If there were not a Vietnam war, we would find some other pretext to keep from channeling the money into what would be the creation of a more democratized, equalitarian society. The war serves as a drain and simultaneously as an excuse: Secretary McNamera recently denied that there was a guns-versus butter issue, and for once in his life he was being honest-but for the wrong reason. There is not a guns-versus butter issue because no one ever expected in the first place that the money not used for the former would go into the latter. Social welfare is some-: thing of a joke–the poor pay for their own medical care, and the corporations pay for their expense accounts. And even these are passed on to the consumers.

This war in Vietnam has what appears to me to be an increasingly dangerous impact on American Society. The fear to speak out against the administration’s policy in the Vietnamese war is becoming more and more evident. With the handy concept of a consensus, it becomes quite easy to identify anyone outside the confines of basic policy as an enemy of the society. Today the State Department sends men all around the country (we had one recently in Detroit) to tell students that the student protest is having no effect whatever–and yet, is not the fact that they are constantly repeating this line a tip-off that the very reverse is true, that protest has made a dent, and that the administration is concerned and would very much like to see it silenced. My point is, now they use manipulation and persuasion; how long until they use force? How wide is the line from a controlled press and kept government officials on one hand and the concentration camp on the other? If you do not think that things are tightening up, look into the outright brutality which occurred at the Vietnam demonstration in Washington just two months ago.

This as I see it is the larger meaning of the Vietnam war in relation to American society: Diversion, taking our minds off the problems at home, make a significant contribution to keep the economy operating (and parenthetically, providing very large profits to key sectors of that economy, and in doing so, bringing about a greater degree of monopolization in that economy than is happening anyway. Study the distribution of defense contracts; note the dividends of General Dynamics, General Motors and Boeing, and tell me America has no economic stake in the war in Vietnam or that the war does not serve in being about a greater internal concentration of wealth than we have seen before), and providing an escape valve for the surplus wealth of America so that America will remain at home a country of inequality, a country of want, and a country of hate. Inequality, want and hate; is there any doubt in your minds that we are that? And is there any doubt in your minds that we need NOT be that with a society more responsive to human needs?

Here, let me add one more aspect as to why we are in Vietnam. By standardizing an immoral practice, we have ceased to make it immoral. That is, we have done everything conceivable over the last three or four years to violate the rights of men, and we have taught the American people how to accept this, live with it, and justify it. Vietnam has become a psychological frontier for American inhumanity, not only for the troops who are there, but for the American people at home: our troops and ourselves have become utterly desensitized to murder, to the deliberate and ruthless slaughter of innocent people, to bringing death without qualm or conscience–and as the murder goes on, we both in the field and at home accept this as a fact of life, as somehow being-part of the normal world, and this in turn makes it possible the entertaining of even more callous murder through bombing irrigating systems, perfecting new weapons systems, and resorting to bacteriological warfare, Vietnam has become one large experiment station where the theoreticians of death and the practitioners of death can combine forces to iron out the kinks in the systematic taking of human life.

I suggest to you that a number of consequences follow from the psychological dimension of the war in Vietnam: not the least is that the more we become immune to the taking of human life, the more unmoved we become to political murder here at home. When will the time come, under a climate of numbness to the means used to attain American objectives, when the weapons perfected in Vietnam can be turned on those who dissent at home? Does that sound far-fetched? I do not think so because we comprehend the number of six million when the Jews were being exterminated in Germany. when the president, the vice-president, the secretary of state, and the secretary of defense tell the American people that we are only bombing military installations they are not telling the truth. I do not enjoy saying in public that the president of my own country has been lass that frank with the American people, indeed it fills me with sorrow and shame, but it is nonetheless the case; for we now have abundant evidence that attacking roads, bridges, and supply depots–if these were ever the objective, have long since given way to the sheer terrorization and elimination of the people. Anything that moves becomes a fit target for American airmen. Hospitals and schools, churches and homes, even a cancer research institute have been destroyed. Our aviators are told that they cannot land with any bombs left over and are urged to use their discretion in dropping them where they think the bombs will do the most good. South Vietnam, too, has been ravished in this way. And when our conventional air power is held to be inadequate, then the super bombers of the Strategic Air Command fly back and forth to Guam and Okinawa with bigger and more terrifying bombs. It would be far too easy to say that President Johnson has blood on his hands, for all of us do in permitting this genocide practice to go on.

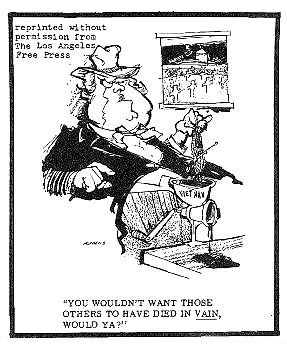

And now that we have learned to live with the daily bombing of innocent people, what will the next step be? Would the bombing of Hanoi bring about waves of indignation to this country? Would the use of nuclear weapons? I ask that you consider the seriousness of escalation, and that you recognize there is a limit to what the other great powers can and will tolerate before there is a major confrontation on the world scene. And I ask that you consider a final aspect to the psychological preparation of the American people. With active intervention an integral part of American foreign policy, will there be resistance–either while the war is going on or if and when it is settled–to intervention in other parts of the world? And given our need for a war economy, and given our need for a scapegoat, and given the central fact of our times–that social revolution and the striving of subjugated peoples to attain their own self-realization will characterize the present and future we already have seen in the world, from 1935 to 1945, what can happen when an apathetic or frightened people capitulate to their government and minorities within their midst become methodically exterminated. Nazi Germany needed a scapegoat to make its system work, and as of this moment, I see too many parallels to give me much comfort. Today our scapegoat is the Vietnamese people. At this very time, all of our resources are going into the extermination of that people. That is the avowed policy of the United States government. How long will it be before we turn on another scapegoat? And what will be the role of the man who has been dehumanized and trained to murder abroad when he returns home? Will he simply return peacefully to civilian life, or will he constitute a paramilitary force of vigilantes opposed to peace, opposed to civil rights, opposed to whatever they have been told outside the consensus?

The war in Vietnam has prepared the American people psychologically in other ways as well. We have already seen this happen in a remarkably brief period of time. Here, I refer to the undoubted fact of escalation. Every month for at least a year now, we have witnessed step-by-step moves to enlarge the war and kill more people. The decisive step of course was the bombing of North Vietnam. Already desensitized to death, the American people have acquiesced in one of the most horrible crimes of recent history. Day in and day out we are indiscriminately killing human beings with our bombs. The American intellectuals were shocked at the bombings of civilian populations by the fascist powers during the Spanish Civil War, but where is the outcry today, when the cold, calculating, wanton murder is many times greater? This crime against humanity does not even make the newspapers anymore; indeed, it-cannot, because of the tight supervision–a polite way of saying thought control–of the news on what is actually happening, The few eyewitness accounts we have indicate such enormities that it would not be hard for even well-meaning people to comprehend the destruction. Just as it was hard to …[gap in original] is there any doubt in your minds that America will continue to intervene in the affairs of other nations? The tragedy of the whole matter, and this brings me to my opening remarks, is that we cannot look at Vietnam in isolation. We must continue to criticize American policy on this concrete issue, but we must also recognize that Viet Nam is a symbol for something more: it is a symbol for what we in America are today, and it is a symbol of what our policy will be in the future–so long as domestic problems continue at home, so long as the American people continue to accept the legalization of murder, and so long as we refuse to permit other peoples to find their own place in the sun.