a film review of

“I Am Not Your Negro” (2016). Director: Raoul Peck; Writer: James Baldwin; Narration: Samuel L. Jackson. 135 min.

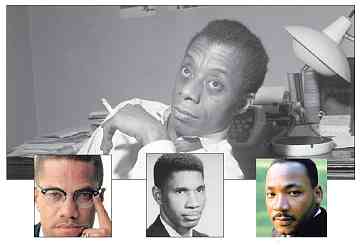

The title of this documentary about novelist, playwright, poet, and essayist James Baldwin is not spoken as such in the film. Where the line is uttered in this excellent film by Haitian-born director, Raoul Peck, Baldwin tells a British audience, “I am not your…” and uses the “N” word to complete his sentence.

It’s not written here because it is the worst word in the English language, one that should never be printed or spoken. Besides its use to demean and dehumanize African Americans in general, it was often the last word heard by a black man about to be lynched, or today, beaten or shot by a racist cop.

Director Peck obtained permission from the Baldwin family to use the author’s 1979 30-page letter to his literary agent describing an uncompleted project about race relations. The text of Baldwin’s letter, originally titled, “Remember This House,” is voiced by Samuel L. Jackson, the highest paid actor in Hollywood. The reference to the movie star’s wealth is to suggest that his participation in this project must, at least in part, be motivated by the realization that no matter how much money he has, as a black man, he can still hear that “famous word,” as I once heard it described.

The film employs historical footage of Baldwin talks and scenes from Selma to Ferguson to draw a chilling portrait of how race still defines America even so long after Baldwin’s death 30 years ago.

This isn’t a biopic. It opens with startling scenes from recent protests against police killings, but quickly defines the film’s touchstones—the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr., civil rights activist, Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X, all of whom Baldwin counted as friends.

Baldwin, speaking through Jackson’s sonorous and dramatic reading, says he is embarking on a “journey to tell the truth.” This simple declaration in America is both subversive and revolutionary. To do so is to attack the fundamental myths of the nation that began as a slave republic, as we are reminded by essential historian Gerald Horne, and which enslaved and bred for slavery millions of human beings, as we are reminded by historians, Ned and Constance Sublette.

The slavers had such a hand in writing the celebrated U.S. foundation document guaranteeing freedom (to some), but which also institutionalized slavery and set up an electoral mechanism for choosing a president that allowed the modern iteration of the Founding Slavers to recently assume the presidency.

The Slavocracy was so integral to the economy of the entire U.S., but particularly the South, that it waged a catastrophic civil war to maintain their “peculiar institution,” the echoes of which are still heard today every time a black person walks down the street.

You may say, “I know the same history as you do. I’m anti-racist.” You’re right. Maybe our readership is the wrong audience for the film although the drama of Baldwin’s words and Peck’s presentation is so intense, witnessing what we think we know is a stark reminder all of us can use.

The film would best be seen by the majority of Euro-Americans who have voted for Republican candidates for president since 1968 solely on the basis of race. However, they probably would have to be strapped to a chair, eyes forced open with clips, “A Clockwork Orange”-style, and forced to see the scenes in this film of their forebears, their historic counterparts, at lynchings, resisting integration in the 1950s, waving White Power signs and swastikas when Dr. King marched in Chicago in 1968, cheering militarized police attacking peaceful demonstrators, and advertisements featuring a slew of appalling Aunt Jemima-style ads.

The images should make those of us who are white—sad, angry, and ashamed, since regardless of our anti-racism, we are the beneficiaries of white supremacy. This is not said to instill guilt. Quite the opposite. It is a call to realize the obligation of the debt we owe by continuing our anti-racist work.

With the election of Donald Trump, we are living in a modern version of a 1970s Rhodesia. A white colonial nation based on horrors that dreams of an imagined greatness that never was. Slavery seemed like a bright idea to bring riches to a few, and an economy that involved millions profiting to some degree, but ignored the human toll.

The one chance for truth, reconciliation, and justice, was smashed following the end of the Reconstruction Era in 1877 by the same social forces which bolster white supremacy today.

The film comes at a time when Baldwin’s writing, received exceedingly well during his lifetime, but having gone into something of an eclipse, is experiencing a recent renaissance. His 1963, The Fire Next Time, spent 41 weeks on The New York Times best seller list and not only spoke for the organized civil rights movement, but also presaged the rebellions that, indeed, brought fire to a nation unwilling to bring about “liberty and justice for all.”

Baldwin’s work approached race and other forbidden topics beginning with his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain; a collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son appeared two years later. His second novel, Giovanni’s Room, caused some outrage because of its explicit homoerotic content. Others that followed, Another Country and Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, dealt with themes of being black and gay overlaid with the violence and unrest of the 1950s and ’60s.

The footage of Baldwin speaking before primarily white audiences contains an electric sense of the period—everything was then open for examination; anything could be changed. Everything needed to be examined and changed. But, the Rhodesians weren’t about to easily give up the world in which they ruled. They killed three men Baldwin loved and countless others just to keep separate drinking fountains and see other people as the word which will remain unwritten here.

There is much in “I am not…” about media representation of black people, from films like “King Kong” or the stereotype frightened or grinning Negroes in Charlie Chan films, TV series like “Amos and Andy,” and ads depicting happy servants. Visuals like this and the 10,000 collectibles in Prof. David Pilgrim’s Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, located at Michigan’s Ferris State University, are part of a contemptible cultural creation which attempted to convince both blacks and whites that the races were in correct relationship to one another.

The majority of whites still support the same policies of repression and believe the same myths. The overwhelming majority of blacks never did; almost none do today. This makes for an explosive social mixture.

It is worth the price of admission alone just to see Baldwin standing amidst a white audience at a 1965 Cambridge University debate declaring his humanity. In The Fire Next Time, Baldwin asks the question, “Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?”

The American Rhodesians are breathing their last. Many of their children want justice as an ethical imperative as much as black children want it as a practical imperative.

The only question that remains is, will the Rhodesians burn the house down on their way out?

Peter Werbe is a member of the Fifth Estate editorial collective. He recently was discharged from his long-time employment and plans to do more than clean out his garage. The books referenced above are Gerald Horne’s The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America, and The American Slave Coast: A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry by Ned and Constance Sublette.