a review of

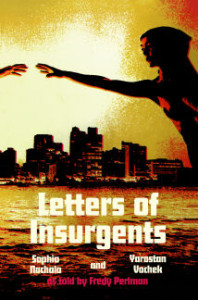

Letters of Insurgents by Sophia Nachalo and Yarostan Vocheck, as told by Fredy Perlman, with a new introduction by Aragorn!. Left Bank Books, 2014, 722pp., $20 leftbankbooks.bigcartel.com

In 1976, Fredy and Lorraine Perlman and other people at the Detroit Printing Co-op published Letters of Insurgents, which at more than 800 pages qualifies as a hefty novel. Although Perlman wrote the book, he didn’t include his name on the cover, instead attributing it to Sophia Nachalo and Yarostan Vochek, the two main characters whose letters make up the text.

Sophia and Yarostan met as teens in the 1950s at a carton factory in an unnamed Eastern Bloc country. They had a brief love affair and participated in an uprising that ended in fellow workers being sent to jail.

Sophia and her family quickly emigrated, and more than twenty years later she sends the first of the letters that make up this book, only to find out in Yarostan’s reply letter that he had spent a lengthy time in prison as a result of the strike. The subsequent nine pairs of exchanged letters unfold the mystery surrounding the pair’s divergent fates after the strike as well as their current lives in revolt.

Though a novel, the story heavily mirrors Perlman’s own life and his experiences working on a college newspaper, participating in urban unrest, and printing in a collective shop. Though he never reveals the countries or dates, the story clearly references the Spanish revolution of 1936-9, the Hungarian Uprising of 1956, and the events in Paris in May 1968.

On the very first page a hint about a missing letter with alleged “strange power” opens a box of questions spanning decades and concluding only at the end of Yarostan’s last letter. Part of the draw is Perlman’s slow unraveling of the circumstances concerning that letter and the effects it had or did not have on Sophia’s former friends.

An epistolary novel, one written in the form of letters, allows a sense of real time to pass between characters’ interactions, time enough for Sophia and Yarostan to reflect upon each other’s words and for plot movement in each of their separate lives. Several periods of time exist within the narrative: stories from older comrades, Sophia’s and Yarostan’s accounts of their shared and separated pasts, and descriptions of present-day events and conversations. They often spend part of a letter responding to the one that they had last received, often in the form of describing the letter-reading gatherings of friends and family, and the political and personal criticisms that make up the surrounding debates.

One of the fundamental themes of the book is the subjectivity of shared experiences. Yarostan and Sophia at first acutely disagree about events that they experienced as teens. Yarostan essentially tells Sophia that the strike in the carton factory, the event that she has held to her heart for all these years as the pinnacle of her life and the beginning of all meaning, was at best a puppet show and at worst the beginning of a descent into an even more repressive government.

This leads to the revelation of the book’s primary tensions: rebellion vs. pedagogy, and intention vs. result. Over and over, we see people’s revolutions transform into the prisons of the future. We also see actions having consequences far beyond the foresight of the originator.

The most dramatic concept in the book involves the removal of social bans as a path to true freedom, summed up by Sabina’s statement, “Nothing is banned. Everything is allowed.”

Whether on the top of a mountain or in an extralegal auto shop, characters break social conventions far beyond the comfort level of most readers. What is hardest to bear about this book is what I would argue is one of its most insightful moments, pushing all but the most libertine of us to wonder if perhaps there are one or two societal rules we would like to keep around. I was introduced to Letters of Insurgents several years ago when a friend brought a selection to share with our anarchist reading group, describing his relationship to the book with the following sentence: “When you read this, you will understand me better.” After reading the entire book and being blown away throughout my adventure with the novel, I agreed with my friend’s description.

Discussing the book with a different comrade during a break between bands at a punk show, I said that it was my favorite novel. He was similarly enamored with it and proposed a completely ridiculous idea: to audio record the entire book–him as Yarostan and me as Sophia–and make it available to download for free.

We had exactly three months to complete this task before he left on an indefinite adventure, so we started meeting every Wednesday night, first having dinner and then recording ourselves reading aloud all night until the small hours of the morning. Because this was all happening in one room, he would edit his previous week’s recording while I read my part aloud, and then we would switch tasks.

This process was extremely time-consuming, but we didn’t miss a week for fear that we wouldn’t finish before his flight out of town. We each spent at least 50 hours on a project resulting in 33 hours of finished audio recording.

It also resulted in something else entirely. In the course of spending time together working on a shared passion, my comrade and I fell in love. Madly, as it were. This began to change the recording process in a qualitative way.

Passionate letters between two fictional characters in a book were infused with the affection growing between the two people reading them aloud. They became love letters between him and me. When Sophia utters words of love, make no mistake that it’s me making a heartfelt statement to the person who was at the time sitting on my bed a few feet away deleting his coughs and stammers from the previous week’s work.

It entered our sex life: we were teenagers caught on the factory room floor, whatever pleases you, Yarostan, and we were brother and sister in the woods, what could be more natural. When we started really arguing, passages of the book entered even then: the old woman with her broom, and Yarostan thinks it’s raining!

The audio version lives on, and I think of my own voice as Sophia’s. A new acquaintance once asked me if I had listened to the recording. “Um, yes,” I said, “I’m Sophia.” This is noteworthy because Sophia is the character I most identify with in the book.

For years, this was a problem because there are several flaws to Sophia’s personality. I’m such a Sophia!, I would say to myself occasionally when exhibiting signs of fear or self-doubt. After discovering that Perlman himself identified most closely with Sophia, however, I became less self-conscious. She is a strong character despite her flaws and not someone to be ashamed of resembling.

I have often affectionately subtitled Letters of Insurgents as “All the Roads to Failure” because of how the narrative follows characters to common ineffective ends. Those active for any substantial length of time have likely seen peers veer into the chasms of party politics, suburban monogamy, and post-traumatic breaks.

And yet, even then, seeing all paths heading clearly into oblivion, we see people creating meaning in their lives and taking inspiring steps to free themselves as far as their daring allows.

“If all the instruments are rotten, what are we left with?”

“We’re left with ourselves and each other.”

–from the text

See related article in this issue: Seattle’s Left Bank Books

Artnoose has been writing and letterpress printing the personal zine Ker-bloom! every other month since 1996. She currently lives in an old Berkeley house with five adults, two kids, and three cats.