a review of

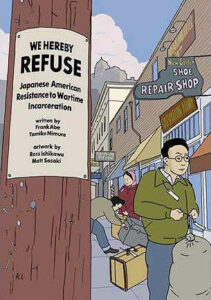

We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration by Frank Abe, script and story; Tamiko Nimura, story; art, Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki. Chin Music Press Inc, 2021

We Hereby Refuse exposes the myth that mass injustice is common in dictatorships, but unlikely in an electoral democracy that has an independent judiciary, a constitution, and a bill of rights.

The book revolves around the personal stories of three narrators caught up in the mass incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans that took place on the West Coast of North America during World War II.

Graphic novels offer a concise manner through which to present political history, particularly social justice and resistance. There is a remarkable clash of artistic styles in We Hereby Refuse by artists Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki. Their engaging narrative goes back and forth between their radically different approaches.

Ross Ishikawa’s art is rendered in a realistic comic style, instantly relatable, spacious and beautifully done in classic colors. His page layouts are ordered and employ frames around the panels.

Matt Sasaki’s style is cinematic, almost a film noir approach using mostly grays and black in his rough almost abstract sketchy line drawings. His page layouts are wild and appear to defy any sense of a grid. The contrast between Sasaki’s visual rage and Ishikawa’s controlled dignity struck me as a perfect metaphor of the complexity presented in the narrative.

Having the two stylistic approaches by these artists strengthens the visual vocabulary of the book in a way that is unique to the graphic novel form and reflects the shifting narrative perspectives of history.

Authors Frank Abe and Tamiko Nimura have created an excellent and vital document of ordinary people responding to circumstances out of their control, but yet taking control by the only power they have left, resistance.

In the telling of the story, Jim Akutso, age 22 of Seattle was studying civil engineering. Hiroshi Kashiwagi, age 19 of Penryn, California was a recent high school graduate planning on attending college. Mitsuye Endo, age 21, of Sacramento worked as a typist at a government agency. None of the protagonists was particularly political until they found themselves drawn into an agenda of state-sponsored racism whipped up by politicians.

The climate of fear and demonization at the time was typified by Mississippi U.S. Congressman John Rankin, a vicious racist and anti-Semite, who said, “I’m for catching every Japanese in America and putting them all in concentration camps.” California’s Attorney General Earl Warren declared, “The Japanese population of California is ideally suited to carry into execution a tremendous program of sabotage on a mass scale.” Warren would later become Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and a liberal icon for his decision on school integration a decade later.

President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942 to evacuate all Japanese, the majority of whom were U.S. citizens, from the West Coast, citing the prevention of espionage and sabotage as the justification.

It was in this environment that the nightmare began in February 1942, with the arrest of Jim Akutso’s father. Later, Jim was also rounded up and sent to a camp, where he refused to be drafted after being classified as a non-citizen. Despite signing a loyalty oath to the United States, Mitsuye lost her government job. Hiroshi was arrested while driving his sick mother to the hospital during a curfew targeting enemy aliens.

Forced relocation is an example of the state using geography as a way to subjugate people. The physical nature of constructing makeshift prisoner quarters for Japanese internees in a fairground is the visual manifestation of state policy. It is not an abstract idea, it is a political threat made real. The wrath of the state is sometimes initially all about optics. Racist rhetoric by politicians prepares the groundwork for the work that is actually done on the ground. This connection is made visually clear in We Hereby Refuse and highlights the strengths of the graphic novel format.

Upon being transported to a relocation camp in Idaho, Jim observes, “I was appalled at my first sight of the desolate camp. The first thought that came to mind was concentration camp. The watch towers were still being finished. Barbed wire was strung all around.”

The state may use public brutality as a means to convey political might, but it can also backfire, as in the recent images of refugee children in cages at the border with Mexico. Incarceration as a political tool exposes the cruelty of power that a liberal democracy is capable of exercising. However, in this case, the round-up of Japanese enjoyed widespread public support, a policy that wasn’t applied to those of German or Italian descent.

As the war dragged on, Army recruiters were sent into the camps to register internees for the draft, but only if they were U.S.-born and agreed to sign an oath disavowing loyalty to the Japanese emperor. However, none of those imprisoned had ever expressed loyalty to the emperor and saw that signing such a statement could be interpreted by the government as an admission of earlier disloyalty and might constitute evidence that could be used to justify their internment.

Internees where the Akutso family was held drew up a statement of principles to present to the camp director declaring that if their rights are not protected by the Constitution, then there is no reason to register. Military police, armed with Thompson submachine guns, raided the camp, but the armed response only deepened the resolve by prisoners to not register.

When Jim Hiroshi refused to register, he was told it was a violation of the Espionage Act that could result in a 20-year sentence.

Meanwhile, Mitsuye Endo’s lawyer brought a law suit against the Army contending that her incarceration was unjustified. In response, Endo was offered a deal that would involve only her release, but she decided on principle to remain in prison and continue with the test case until all prisoners were released.

Hiroshi and others protested for better living and working conditions and elected representatives for a negotiating committee and organized a 5,000-strong silent demonstration that surrounded the administration building.

The resistance to the draft continued as prisoners were urged to break the law by not registering. One mother summed up the situation, “Our sons are no less loyal than any other American…it’s the country that’s not loyal to them!”

A hunger strike by prisoners lasted several weeks until authorities caved, fearing further bad press.

We Hereby Refuse is a grim reminder of the legacy of American racism, one going back 500 years that the U.S. refuses to come to terms with. This lack of reckoning will surely see more tragic and heartbreaking injustice to come. But this is the political and social importance of presenting history like We Hereby Refuse in a graphic form. It is perhaps the future of activist art.

Although the stories in We Hereby Refuse took place over 80 years ago, they remain incredibly relevant and act as a cautionary tale for contemporary times. Resistance is not a dated concept, it is an essential act in a functioning democracy, especially as the world appears to be lurching towards authoritarianism.

David Lester illustrated 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike and is the guitarist in the underground rock duo Mecca Normal.

Related

Concentration Camps USA, FE #329, Summer, 1988