Introduction

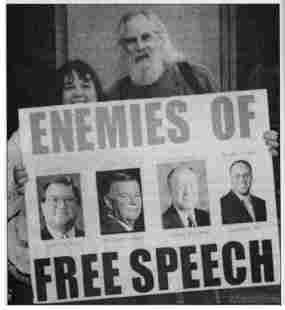

From September 10-15, the Cascadia Media Alliance hosted a Reclaim The Media Convergence in Seattle. Held during the week of the annual convention of the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), this occasion was an opportunity to protest the corporate-driven policies of the NAB/FCC/NPR triumvirate, as well as to gather for our own grassroots shadow convention. Community media activists from all over North America descended upon Seattle to hear speakers, do workshops, strategize and bounce off each others’ creative energy. By the end of the convergence 10 free radio stations had been set up just 2 band widths apart on the FM dial in open defiance of the censorious 3 bandwidth low power fm requirement of the FCC. This rule has in effect created a situation in which LPFM stations are not legally feasible in urban areas like Seattle. The eclectic programming mix of these pirate stations featured everything from guerrilla radio broadcasts of the FCC actually battering down the doors of Free Radio Austin, to a satirical piece about Clear Channel by Mark Hosier of Negativland, to a series of 3 minute airplay spots on the subject of “media and democracy.” I was invited to kick off the week’s events with a presentation at the Seattle IMC. Focusing on the affinities between anarchism and surrealism in relation to media activism. My talk, upon which the following article is based, consciously avoided the self-congratulatory approach of keynote speakers David Barsamian and Amy Goodman, and instead sought to raise thorny strategic questions for anarchists involved in the media democracy movement.

Tuning in to the Media Dreamscape

As anarchists, we must ask ourselves whether our goal is to achieve the institutionalization of our radical demands vis-a-vis radio in particular and media in general OR alternatively to demand the radical transformation of that which has been appropriated and institutionalized.

In answering this question, we can start by addressing the title of this convergence, Reclaim The Media. In one sense, this title is a misnomer. While there have been some distinct turning points in early radio history where things could have gone in a more populist direction, when it comes to radio in particular and broadcast media in general, we are really not reclaiming what was once ours in any simplistic sense.

Rather, we are seizing or taking back what has been stolen from us before the NAB or Clear Channel ever existed. In the case of television, this theft was structured into the system right from the start. There was no golden age in which we controlled the broadcast media, so strategically we cannot reclaim what we never had.

However, since the channels of communication have increasingly been strip-mined and clear cut and the mediascape brutally mauled in recent years, we can fruitfully recall a history of struggle: of opportunities lost, inspiring moments of resistance, culture jamming breakthroughs, and underground wellsprings of oppositional media that have surfaced, and some of which have survived and flourished, over the years.

Aside from these episodes in radical history, what we are reclaiming is our very ability to imagine a broadcast media that satisfies our deepest desires.

Surrealist Don La Coss has illuminated the affinities between radio and the imagination in his “Antennae of Magnetic Midnights: Surrealist Guerrilla Radio” piece which was circulated as part of a zine designed for the Reclaim The Media gathering:

“When you fall into sleep, your consciousness concludes its broadcasting day and signs off of the air. At that point, transmissions normally not heard during waking hours become noticeable; as you slumber, your mind scans these distant transmissions from the unconscious, occasionally tuning one in clearly enough to become a dream. At its deepest core, the human psyche radiates a vast, natural reservoir of instinct, spontaneity, cooperation, creativity, love, and open sexual response that communicates most clearly when the static buzz of everyday living is shut down for any length of time. Uncensored and unpredictable, these broadcasts that blast from the unconscious may not always be pretty or pleasant, but like the direct speech of Radio Alice and the passionate truths of Radio Libertaire, they are honest, open, and free from outside interference and distortion. Upon awakening, your conscious mind resumes broadcasting again and jams those unconscious transmissions with the 60-cycle hum of daily activity. Though mostly inaudible, the illegal broadcasts of the unconscious continue without pause, biding time until the conscious mind is turned off again, as it inevitably will.”

Given this insight, it seems to me that at its most imaginative our radio activism would be tuned into these dream broadcasts rather than built upon the nostalgic myth of once having been in the driver’s seat in relation to broadcast media.

Thriving on dreams of revolt, surrealism has been a part of the radical political imagination since the Twenties, though even many radicals do not recognize the role of imagination as pivotal to social transformation and even dismiss its value by contemptuously labeling it as “unrealistic.”

Given the depth of what surrealists demand—the transformation of reality itself—their strategies tend to be, like those of anarchists, revolutionary rather than reformist. Surrealism is not populist, and its demand for an end to the artificial dichotomy between dream and reality cannot be subsumed in the rhetoric of social democracy or recuperated in the bureaucratic language of corporations or regulatory agencies.

As surrealist Penelope Rosemont has summed it up, “Surrealism is what happens when poetry and life dare to be one and the same.” Like anarchists, surrealists demand the impossible, pushing beyond the already existing boundaries of the possible into the uncharted terrain of the Marvelous. Instead of confining themselves to the pragmatic politics of the possible, which are rooted in a miserablist acceptance of so-called “realistic” limitations, surrealists seek to create fault lines in our consciousness about what might indeed be “possible” in a world of unfettered imagination.

Formulating a Radical Media Politics

How then might a radical media politics that recognizes the worth of both surrealism and anarchism be formulated? Instead of expanding upon a foundation of populism, we would be seeking out those elements of refusal which connect with both anarchism and surrealism, building upon them, and seeking insights that might inspire us in exciting new directions while simultaneously raising the stakes of what is desirable.

Unlike that other reclamation movement, Reclaim The Streets, there has never been a living historical practice rooted in “the commons” for us to call upon as justification for our demands in relation to the broadcast industry. So instead, media activists often use the word democracy. However, democracy is a very problematic term. In the US, it has been associated with “the public interest” in the case of regulatory agencies such as the FCC, but the bureaucratic concept of “the public interest” differs markedly from that of “the commons.” Aside from the tangibility of a concept literally rooted in the earth, “the commons” implies collective ownership in a way that “the public interest” does not.

Instead of the direct democracy of “the commons” concept, we get the indirect democracy of the FCC’s stewardship of the airwaves. While they claim to act in our best interests, in reality the agency has been captured by the very corporate interests it supposedly exists to regulate on the public’s behalf. However, though historically an inaccurate metaphor for the airwaves, I believe that we can poetically use the metaphor of “the commons” to spark our resistance to what is increasingly being seen as a new form of enclosure not on the land but in relation to the airwaves that surround it

At the tail end of the last century, I sought to address the increasing territorialization of the airwaves and enclosure of radio in Seizing The Airwaves as a touchstone for envisioning an oppositional free radio movement engaged in squatting the airwaves through the direct action strategy of radio piracy. Since then, in his new book, Tearing Down the Streets: Adventures in Urban Anarchy, Jeff Ferrell engagingly places the free radio movement within the context of the “commons” by examining such other challenges to restrictions on access to public space as Reclaim The Streets parties, Critical Mass rides, graffiti writing, busking, skateboarding and other oppositional forms of DIY cultural resistance.

As he puts it, “Pirate radio operators and street musicians would remind us that the streets exist not just as physical space, but as a contested ether of sonic space and communication, and would therefore point to the role of local governments and the FCC in closing down the city’s lively cacophony.”

Let’s take Ferrell’s skateboarding example as a jumping off point to illustrate that public space in urban areas is increasingly seen as contested terrain. I just recently moved from Springfield, Illinois to British Columbia, and for the last few years before I left Springfield there was much public debate on creating an officially planned municipal skate park. Like many places in the US, in Springfield, if you’re conservative you’re considered normal, if you’re liberal you’re considered radical and if you’re radical, you’re considered crazy. Well, I had the crazy idea that creating a skate park was not the right strategy for radicals. I see skate parks as essentially a form of containment rather than a means of liberating the streets and public space from the yoke of policed corporate culture. Yet, faced with a hostile environment where conservatives routinely attacked skaters as degenerate scum, and cops arrested kids on the flimsiest of pretexts for invading the sacred downtown space reserved for Lincoln tourists, state government bureaucrats and their cohorts in Springfield’s state legislature; both liberals and radicals (even including a few that identified their politics as anarchist) argued for the legalization of skating via skate parks.

In so doing, they accepted the circumscribed conditions that established these parks as a sanitized replacement for (rather than an addition to) free access to city streets. As if to confirm my worst fears, once I arrived in my new home in BC, I heard that the nearby city of Courtenay was justifying its threat to increase the repression of downtown skaters by reference to skate park availability. The city was claiming that since it had a skate park where the activity was permissible (albeit for a fee), kids who had the temerity to do their skating on the downtown streets should be harassed and fined.

This approach immediately struck a nerve in me in terms of my Springfield experience, and the more I thought about it I began to smell the stench of the “protest pens” that have become a regular fixture of Democratic and Republican political party conventions in the States where the aim is not to facilitate protest but to control it. In opposition to such urban “cleansing” strategies, not only is my argument against skate parks in keeping with Ferrell’s, but with a piece called “Against The Legalization of Occupied Space,” which is a Venomous Butterfly pamphlet-length critique of the government-sanctioned Italian social center movement by two dissident Italian anarchists who go by the names of El Piso Occupato and Barrochio Occupato. They argue against a legalization strategy and in favor of increasing the number of illegally occupied squats and the growth of liberated social space in general as a more appropriately anarchist strategy. Such an approach in turn is consistent with what surrealists mean by “absolute divergence.”

In this same sense, we must ask ourselves if our goal is institutionalization or deinstitutionalization? This is in essence the question I raised in my widely circulated “LPFM Fiasco” article first published online in Lip Magazine last year. In relation to the great debate then raging around LPFM as a strategy, I argued in support of anarchist pirate radio stations within the micropower movement which preferred to keep their stations unlicensed in order to avoid the co-optation of the free radio idea. Their emphasis was on eluding both government and corporate control. LPFM, on the other hand, is a populist rather than an anarchist strategy. As I saw it then and continue to see it now, Kennard, the FCC Commissioner who originated the LPFM program, was slyly offering us the carrot of licenses as a carefully laid trap to regain his agency’s control of the airwaves at the height of the free radio movement’s insurgent challenge to the licensing system through acts of civil disobedience and active resistance. His goal was the liberal one of enclosing the micropower radio movement within the bureaucratic guidelines of government regulation while continuing to expand upon his use of the stick to crack down on illegal stations.

Not coincidentally, his enticements to normalization through legalization were cleverly designed to divide the movement. Consequently, I am not contending that LPFM advocates and unsanctioned radio pirates can’t work together to “fight the power” in certain ways, and the Reclaim the Media convergence did offer us opportunities to strategize together. Similarly, we must avoid being turned against one another. The FCC would like nothing better than to play “divide and conquer” within the micropower radio movement. Nor do I want to play the tired game of “more anarchist than thou.”

All I want to do at this juncture is to clarify differences within the movement in relation to our long and short term goals, whether explicit or implicit, examine the strategies that diverse types of activists choose to achieve them, and figure out ways in which we can engage with one another in creating a strategy that is mutually reinforcing rather than unnecessarily divisive.

Now, of course, with Powell as the conservative chair of the FCC, even the containment-oriented LPFM program is in jeopardy, much to the delight of the NAB and NPR lobbyists whose efforts against it have paid off so handsomely.

Recognizing the above dynamics, what’s an anarchist to do? Some anarchists prefer not to involve themselves in reformist struggles, while others do so cautiously and always keep in mind that mere legalization can never be the final goal. Such struggles are most valuable from an anarchist perspective if a grassroots movement can use them as a launching pad for making ever more radical demands rather than giving in to the desperate compromises of the bureaucratic survival game, of just a few more crumbs from the master’s banquet table please.

Returning now to the similarities between radio piracy and the squatter movement, currently, in Vancouver and Victoria, BC, there are housing struggles going on over the issue of “social housing.” As these cities increasingly are subjected to gentrification, the issue of access to affordable housing is as much of a life or death matter as access to health care. In recent months, vacant buildings which had been designated as future social housing sites have been squatted when the new right-wing government refused to deliver on earlier promises to provide housing there. Yet, while occupying a building, and then returning to occupy the street in front of the building when evicted by the cops, are unquestionably militant tactics, they do not necessarily have anarchist consequences. For this reason, some anarchists among the squatters have been pushing for keeping these squats autonomous rather than seeing their efforts coopted by government in the form of bureaucratically administered public housing.

In our protests we must ask ourselves, as anarchists, ‘How do we create a situation in which the public belief in government solutions to political problems is undermined rather than ending up reinforcing the popular attitude that if only we had a more responsive government everything would be OK?’ And as a surrealist question we might add, ‘How do we go beyond mere realism in both our tactics and our overall strategic demands?’

These questions, of course, were important ones to address at our Reclaim The Media events in Seattle. Rather than creating the illusion of a once upon a time broadcast media democracy, in my opinion, we should be calling for nothing less than a radical break with the trajectory of broadcast media development ever since the early days of its existence at the beginning of the twentieth century.

For me, the need for such a radical break cannot be automatically derived from a populist slogan like “media democracy” without some further explanation. For one thing, we must continue to be about creating galvanizing imagery and making artistic statements that break people out of their consumer trance and move them into action. Surrealist Franklin Rosemont put it nicely when describing the Bread and Puppet Theatre back in 1989, as if in anticipation of the widespread use of puppets in street demonstrations that was to come in the global justice movement of the following decade:

“Peter Schumann and his friends have sounded the tocsin for a resurgence of the best kind of magical utopianism: reveries of a wildly desirable yet fully realizable world beyond the paralyzing dichotomies that enforce a system of exploitation and horror…Here the crisis of consciousness meets the vengeance of dreams head-on in the dazzling promise of a new day. Marvelously subversive, subversively marvelous, these puppets inspire a life larger than life, a jump for joy beyond all misery, a future worth its weight in light.”

With this in mind, we must always remember to include tactics that rupture mass mediated consensus reality by freely making use of the surrealist arsenal of mad love, poetic revolt, black humor and creative sabotage to festively lift the veil on the NAB’s corporate face by debunking their claims that they are only giving the people what they want, that in fact they are operating in what they call the public interest.

Hey, they do audience-marketing studies, you know, and the “diverse” consumer demographics of focus groups determine the mindshare strategies which drive programming content. Isn’t this democracy? Why, it’s even multicultural. Therefore, along with all the Reclaim The Media emphasis on making the corporate media more accountable should be an emphasis on the other self-determination slogan popular among radical media activists: “Become The Media-DIY”.

So where does surrealism intersect with activism in a way that is compatible with anarchism? According to African American historian, cultural critic and author of Race Rebels, Robin DG Kelley, in a talk he gave to University of North Carolina students in September of 1998, and later expanded upon for his new book, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination:

“Above all, surrealism considers love and poetry and the imagination as powerful social and revolutionary forces, not as a replacement for organized protest, for marches and sit-ins, for strikes and slowdowns, for matches and spraypaint. George Clinton used to say that we need to ‘dance our way out of our constrictions.’ He was being funny but dead serious. Whether we call it dancing, or dreaming, or making poetry, we need to recognize that the hardest work we have before us is breaking the chains of imaginative slavery. If we want a new society, we have no choice but to supersede the dominant reality—to imagine a different relationship not only to the economy, but also to time, to work, to the natural world, to each other.”

Superseding reality

By superseding existing reality, we must break with the current injunction to ‘keep it real.’ Of course in contemporary Hip Hop lingo the power of ‘keepin’ it real’ means many things: it is a challenge to commercialism, a recognition of the ‘ghetto’ as a site of creativity, a call for solidarity with oppressed classes. But if we believe in revolution, we need to move beyond the real and to make it surreal.”

To quote Lautréaumont, “Poetry must be made by all.” Yet, surrealists are not talking about having more trendy poetry slams, but about creating a world in which people’s lives can be made more poetic, where poetry is something that you live rather than something you just read or even write. Since this emphasis on the poetry of everyday life can be an appealing vision to both anarchists and surrealists, those who find themselves at home in both milieus might consider how our media activism strategies reflect that affinity in the process of fanning the insurrectionary flames which will light the path to marvelous freedom.

—Denman Island, BC, Fall 2002

All quotes are from the book Surrealist Subversions: Rants, Writings and Images by the Surrealist Movement in the United States (Sakolsky, ed., Autonomedia, 2002) except for those of Don La Coss and Jeff Ferrell as noted above.

Ron Sakolsky’s guerrilla radio statement, broadcast September 2002

“This is Ron Sakolsky and I’d like to tell you something about media and democracy.

“As an anarchist, my affinity with democracy is not about voting for someone to better represent us, but rather taking action to directly represent ourselves. Just as I don’t consent to being ruled by some politician, no matter how Green, Left or Libertarian; I don’t trust some professional media talking head to frame my reality for me. My conception of how media and democracy are related involves a radical critique of both.

“I know a surrealist poet named Jayne Cortez, who says in one of her poems:

“‘Find Your own voice & use it

“Use your own voice & find it.’

“So if we are to take the science that Jayne is droppin’ on us seriously, we’ve got to lift our collective voices against injustice and on behalf of our dreams for a world of freedom. And when we do this together, we are each stronger for it because we find our own voices in the process of passionately using them in our own chosen ways to resist oppression and to insist on liberation.

“Now when we compare this radical vision of democracy to the miserabilism of our currently mediated lives, we must inevitably confront the gap between the fatally compromised illusions that comprise what is called political reality and our own brightly burning desires for personal and social autonomy and an end to hierarchy and domination.

“It is then that we begin to question our socially assigned roles as passive citizen/spectators, and to demand control over the means of cultural production, representation and distribution which today are largely the domain of the corporate and public media giants.

“In so doing, we emerge from the velvet prison of consumerism and market demographics and become alive to revolutionary possibilities outside the one world of global capitalism. As we awaken from our media-induced trance, we unleash the insurgent power of the creative imagination, shake off the shackles of the reality police, and break the silence of cynicism and despair.

“‘Find your own voice & use it.

“Use your own voice & find it.’

“For the Cascadia Media Alliance, this is Ron Sakolsky.”