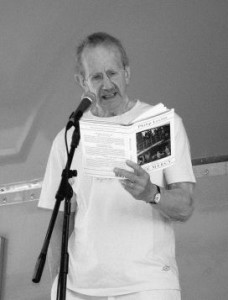

Levine’s many poetry books are flying off bookstore shelves, in which readers will encounter poems about working class Detroit where Levine worked building transmissions at a Cadillac plant, plus others about anarchists in Spain such as the one on this page. In interviews, Levine talks about being drawn towards anarchism because of an affinity with the Spanish Revolution. He has written about modern Spanish poets such as Antonio Machado and Garcia Lorca, but also anti-fascist anarchist militia leaders like Buenaventura Durruti and Francisco Ascaso.

The post of laureate, which runs only from October to May, is mostly ceremonial but draws public attention to the author’s work. The designate is chosen by the Library through consultation, in part, with the current laureate, who was W. S. Merwin, an engaged Buddhist and 1960s anti-war activist.

In describing his works, which earlier were often “gritty, hard-nosed evocations of the lives of working people and their neighborhoods,” Levine says his poems have softened somewhat. He told The New York Times, “I find more energy in my earlier work. More dash, more anger. Anger was a major engine in my poetry then. It’s been replaced by irony, I guess, and by love.”

Levine, now 83, has numerous books in print. His volume, The Simple Truth, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1995.

On the Murder of Lieutenant Jose Del Castillo

By the Falangist Bravo Martinez, July 12, 1936

When the Lieutenant of the Guardia de Asalto

heard the automatic go off, he turned

and took the second shot just above

the sternum, the third tore away

the right shoulder of his uniform,

the fourth perforated his cheek. As he

slid out of his comrade’s hold

toward the gray cement of the Ramblas

he lost count and knew only

that he would not die and that the blue sky

smudged with clouds was not heaven

for heaven was nowhere and in his eyes

slowly filling with their own light.

The pigeons that spotted the cold floor

of Barcelona rose as he sank below

the waves of silence crashing

on the far shores of his legs, growing

faint and watery. His hands opened

a last time to receive the benedictions

of automobile exhaust and rain

and the rain of soot. His mouth,

that would never again say “I am afraid,”

closed on nothing. The old grandfather

hawking daisies at his stand pressed

a handkerchief against his lips

and turned his eyes away before they held

the eyes of a gunman. The shepherd dogs

on sale howled in their cages

and turned in circles. There is more

to be said, but by someone who has suffered

and died for his sister the earth

and his brothers the beasts and the trees.

The Lieutenant can hear it, the prayer

that comes on the voices of water, today

or yesterday, from Chicago or Valladolid,

and hands like smoke above this street

he won’t walk as a man ever again.

What do you mean when you say you’re an anarchist?

If you’re going to allow people to make all the important choices about their lives you’re going to be relying on them to make decent choices. If people are going to make unwise and disgusting choices that tyrannize their brothers and sisters, then they have violated a profound anarchist tenet: you don’t tyrannize other people. In accepting your own freedom you have to grant others theirs. One basis of anarchism is the appalling confidence people will act decently.

— Philip Levine, from an interview with David Remnick (Michigan Quarterly Review [1980]).